|

UCLA, UC Berkeley, and UC San Diego are set to reduce international student intake in favour of admitting more Californians, backed by a state-funded budget to deal with the anticipated revenue loss. Within five years beginning fall 2022, these three campuses are set to reduce non-resident student enrolment by 7% to make room for approximately 4,500 Californians. The Los Angeles Times reports that the UC system wants to admit 6,230 more local freshmen in 2022. This comes after receiving a record number of applications for fall 2021, “in a year of high emotion and myriad questions over the admissions process and frustration over the lack of seats for qualified students.” This will come at the cost of 900 international students annually across the three UC campuses. It is expected to accommodate UC admission reforms, thus reangling the public research university system as one that prioritises qualified Californian applications. This budget support should help cover the financial losses from reduced international student intake — around US$30,000 per student and US$1.3 billion collectively each year. Chancellors say the UC system stands to lose much more latent benefits. “As state funding declined, the enrolment of non-resident students helped offset tuition costs for California students and provided revenue that enabled us to improve educational programmes for all students,” said UC San Diego Chancellor Pradeep Khosla. He maintained that non-resident students are enrolled only in addition to qualified California students, not in place of them. Their tuition — which is significantly higher than what domestic students pay — helps cover faculty recruitment, library collections, instructional equipment, and additional courses, which keeps classes small and focused. Lower international student intake, lower revenue. Under this budget plan, California is set to fund the admission of more local freshmen in fall 2022 — that’s US$180 million to cover the UC and Cal State enrolment expansion. The state will also provide US$154 million for 133,000 community college students in fall 2021. On top of that, a US$2 billion fund will be created exclusively for student housing. From 2017 onwards, international student intake at UC universities has been capped at 18% — except for UCLA, UC San Diego, UC Berkeley, and UC Irvine. UCLA Academic Senate chair Shane White calls for this rule to be analysed, along with other fundamental issues on international student intake within the state university system. UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ added that the current state allocation does not cover the actual cost of instruction. “Replacing out-of-state students with Californians thus creates a budget gap that needs to be filled,” she explained. “Even more important, out-of-state and international students contribute significantly to the diversity of the student experience, and the majority of these students remain in California after they graduate.” The UC network includes ten campuses, five medical centres and three national labs. Californian universities have the highest international student intake in US. Over 160,000 are enrolled in the state’s institutions, with over 8,000 in UC San Diego. An estimated 20% to 25% are studying remotely from overseas during the pandemic, but not all may be returning. Though international student intake may soon drop in these universities, foreign interest is still at a high. According to the Keystone Academic Solutions’ State of Student Recruitment USA 2021 report, 36% of international students choose California as their preferred US study destination. This suggests that international students will soon face stiffer competition when applying for their preferred UC university. In May, the UC system proposed that every student returning from overseas must first receive a vaccine approved by the World Health Organisation. This includes Pfizer/BioNTech, Astrazeneca-SK Bio, Serum Institute of India, Janssen, Moderna, and Sinopharm. “We understand that there may be some remote instructions available as well because we do have learners from all over the world whose circumstances continue to evolve, but the intention is to highlight and continue to return to in-person learning as many ways as we possibly can,” added Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Alysson Satterlund. Source: Study International.

0 Comments

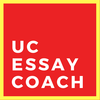

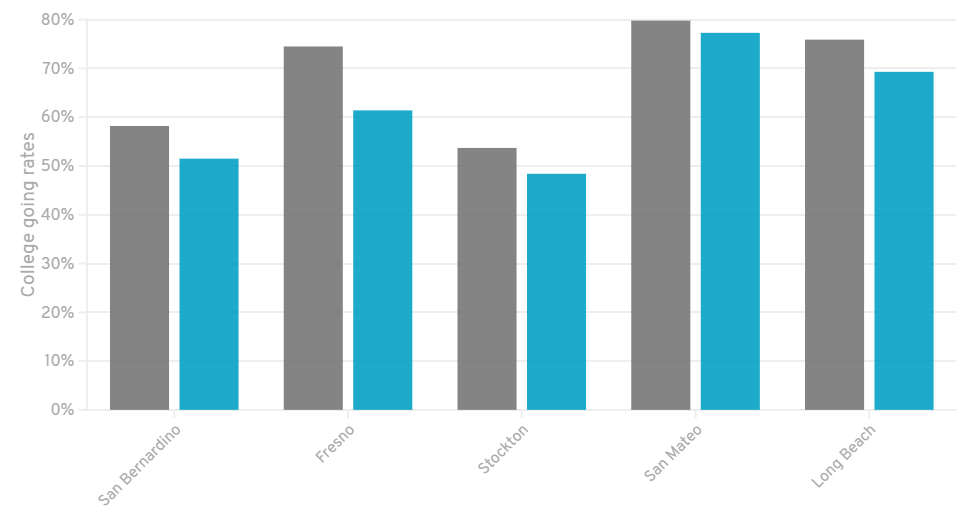

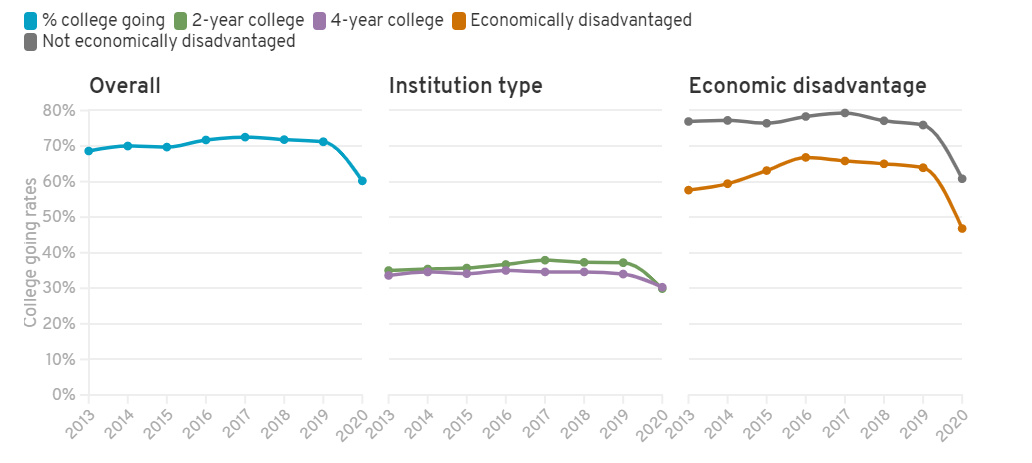

In early June, 19-year-old Brian Cruz was on a break from his warehouse job at Amazon, listening to music. He scrolled through the messages on his phone and saw an email from the college and career center at his old high school in Hemet, a high desert town in Southern California. Even though Cruz graduated from Tahquitz High School last year, the email invited him to make an appointment with a school counselor. Last spring, Cruz decided to put off college and work while he waited out the pandemic. But a year of packing boxes at Amazon and a lifetime of seeing family members work manual labor made him anxious to go back to school as soon as possible. “I was happy to get that email, because I really didn’t know what to do,” he said. Cruz is one of the first students to participate in College Comeback, a counseling program launched by the Riverside County Office of Education at the end of May. A team of six spends 25 hours a week reaching out to the high school class of 2020 after data revealed that 2,300 fewer students — a decline of around 8% — went to college in fall 2020 compared to the year before. The numbers from Riverside County mirror trends in other parts of the state and the country. Nationally, college going rates for students straight out of high school were down 13% overall and 22% at community colleges in fall 2020, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, a non-profit that tracks enrollment data. Experts attribute the enrollment decline to the COVID-19 pandemic and aren’t sure how soon — or whether — those numbers will bounce back. “That’s one in five freshmen who would have been expected to go to a community college this fall that simply didn’t show up,” said Doug Shapiro, executive research director at the Clearinghouse, during a presentation for the Education Writers Association in May. Coming back A few days after getting the email from the school counselor, Cruz logged onto a Zoom appointment with counselor Yuri Nava. He told her he’d been accepted to University of California Riverside last year, but didn’t enroll after he found out classes would be online. Nava informed him he’d missed the Nov. 30 deadline for the upcoming school year, so he’d have to wait until fall 2022 to start at UC Riverside. No one had told Cruz that he had the option to defer his admission a year, he said. Nava then walked Cruz through his options, encouraging him to think about community college. College going rates Five of California's most populous public school districts provided data for college-going seniors for 2019 vs. 2020. She worked with Cruz on filling out his financial aid application, also known as the FAFSA, and booked another appointment to complete his application and select classes at Riverside City College. “I don’t know where I even have to begin,” he said. “I’ve been talking to people from (colleges) and they haven’t really been very clear on what I actually have to do to get into the school and choose the classes. I mean I tried it, but I really couldn’t do it myself.” College Comeback has been a boon to students like Cruz, but time will tell how many students the program will be able to reach. Outreach to students last summer showed how challenging it can be to get large numbers of students to reengage in higher education, but also how effective one-on-one counseling can be for individual students. How it works After they graduate, students lose the support they’d normally get from their high school counselors. College Comeback is the first program of its kind in California, specifically targeting recent graduates who want to go to college but don’t know how. Students who graduated from Riverside County high schools last year can sign onto a booking website to make different types of appointments to explore postsecondary options, fill out a FAFSA or California Dream Act form for undocumented students, fill out a college application and learn about career and technical programs or military service. The county has paid counselors like Nava a stipend to take on the extra workload via money previously allocated to things like travel. Whereas high school counseling often involves group workshops, the alumni program focuses on individual appointments, said Catalina Cifuentes, director of college and career counseling for Riverside County. Because counselors are also trained mental health professionals, they also provide social and emotional support for students who might be facing challenges that impact their educational choices, Nava said. College Comeback also collaborates with colleges and universities and stays in touch until the student has registered for classes. “We don’t want the students to get a run around,” Cifuentes said. The program got off to a slow start because district leaders were worried about diverting attention from the current class of seniors, but currently has approval to continue for the foreseeable future, according to Cifuentes. Education experts say there’s ongoing need for postsecondary support for all graduates that will persist beyond the pandemic. Statewide, almost 22,000 fewer seniors from the class of 2021 have filled out the FAFSA compared to this time last year. This summer, Riverside counselors will also be working with 2021 graduates to make sure they complete all the steps necessary to go to college this fall. A big problem Clearinghouse’s Shapiro said the college-going data is alarming. “It continues to get worse when you drill down into some of the demographics within that,” he said of the national data. “For Black students, Latinx and Indigenous students, in particular, the declines were almost twice as steep.” San Diego County, for example, saw a drop in college-going seniors by around 11% with around 16,000 of the county’s 26,500 graduates headed to college in 2020. The drop was even more “catastrophic” for some groups: 17% for low income students, 24% for Native American students and 33% for English language learners, according to Shannon Coulter, director of research and evaluation at San Diego County Office of Education. San Diego County college going ratesBoth 4-year and 2-year institutions experienced a drop in enrollment. Graduated high school seniors who were economically disadvantaged were slightly less likely to enroll in college than other students. While experts hoped students who disappeared in the fall would return in the spring, so far that’s not the case. Recent spring enrollment data from the Clearinghouse show similar declines in enrollment between this year and last spring. “The effect has been that this pandemic has been exposing and widening existing inequities in our society, even to the extent of reversing the progress that we’ve made in recent years around closing the equity gaps in terms of access to college,” Shapiro said. That has borne out in Riverside County, which had one of the worst college-going rates in California back in 2013 at around 54% percent, according to Cifuentes, the Riverside County counseling director. Through concerted efforts aimed at improving college going, including professional development for counselors and a huge push for FAFSA completion, the county had been able to boost college enrollment rates to more than 60% as of 2019. But between 2020 and 2019, the enrollment rate dropped almost back down to the 2013 levels. Cifuentes said the pandemic “erased all of the progress we’ve made in the last seven years.” Shapiro said that colleges need to figure out how to reach not only current high school seniors but also those who graduated last year. “They’re disconnected now from education,” he said. “These are students that if they don’t make it back, they’ll be disadvantaged in terms of their skills, their employability, their earning potential. Not just themselves, but their families, their communities, and our whole country… will suffer from that.” Troubling declines While statewide data isn’t available, the number of California high school graduates from the class of 2020 who went to college dropped in several of the state’s most populous districts compared to the year before, according to Clearinghouse data provided to CalMatters. All eight districts and four counties for which CalMatters viewed data saw a decline in graduates going directly to college, ranging from 2.5% in San Mateo Unified to 13.1% in Fresno Unified. Districts with a higher share of low-income students or students enrolling at community college saw bigger drops. That translates into thousands of California students who didn’t go to college last year. In Los Angeles Unified, the largest school district in California, college-going rates decreased from 68% to 59% between 2019 to 2020, a drop of more than 2,600 students, according to Clearinghouse data. Oakland Unified dropped 11% with around 46% of its 2020 grads headed to college, while San Francisco Unified reported a 6% decline. The decline in college going rates has significant implications for students, colleges and California. Following national trends, California has made significant progress over the last several years in improving college going rates, especially for groups that are historically underrepresented in higher education, so the recent declines are troubling, said Hans Johnson, director of the Higher Education Center at the Public Policy Institute of California. “We know that going to college is one of the most important ways that we continue to achieve economic mobility in our state,” he said. Johnson said the question is how many high school graduates who didn’t go to college because of the pandemic will eventually go back. “Anytime a student stops out, for whatever reason, they’re less likely to ever return [to college], even if they have good intentions,” he said. Struggling and juggling Students and counselors cite a number of reasons for the decline. Many, like Cruz, wanted to avoid online learning or didn’t have reliable Internet access, while others became primary wage earners in their households, or took on care responsibilities. Some students who tried to enroll in the fall ended up dropping their classes because they struggled with online classes. Colleges have also reported increases in students who are only attending part time. Some members of the class of 2020 are taking the more traditional “gap year,” where they’ve been admitted and defer a year. At Stanford, for example, 378 first-year students — or around 20 percent of the incoming class — opted to wait until fall 2021. One of them was Langston Buddenhagen, a 2020 grad from Oakland Tech High School. He wasn’t thrilled at the prospect of spending his first year of college sitting in front of his computer. “The main goal [of my gap year was] to avoid the COVID disruptions and try and wait out as much of it as I could,” he said. He started his own business tutoring younger students and volunteered with a task force in Oakland working on police reform in the wake of the George Floyd murder. He also interned with the San Francisco district attorney’s office. Nineteen-year-old Andres Martin, a graduate of Skyline High School in Oakland, had applied and been accepted to several out-of-state colleges and other institutions in Southern California. But when the pandemic hit, his flight attendant mother was unable to work and his dad, an electrician, had a hard time finding jobs. As a result, Martin had to reconsider where, and whether, he wanted to go to college. He got into UC Riverside, but decided it would be too expensive to move so far away from home. “It didn’t seem like I had much of a choice of where I could go,” he said. Like many students, Martin also worried about his ability to be academically successful with remote learning. “I knew that I would keep struggling since in the pandemic, it was really hard to stay motivated, stay focused, stay on task, just not being in a classroom situation,” he said. Martin considered community college, but realized he’d have to study there for two years and transfer. He decided to instead focus on community service and a fellowship program where he learned how to code in order to strengthen his college applications. He applied again for fall 2021 with support from College Track, a non-profit he’d worked with throughout high school that helps students apply to and transition to college. Now, he’s planning to study computer science next fall at UC Santa Cruz. “I’m pretty excited to be able to get back on campus,” he said. Impact on colleges For fall 2020, overall enrollment across the University of California’s nine undergraduate campuses remained relatively flat, but the system also enrolled a record number of in-state residents. The California State University system also had its largest-ever student body for the fall 2020 term, collectively enrolling 485,549 students. But COVID-19 ravaged California’s community colleges in California — which vastly outnumber UC and CSU campuses — to the tune of an 11% drop in students, according to system data. This has been especially problematic in regions where most students go to community college. Santa Cruz County, on the central coast, had a drop of 7% in college going and Shasta County, in Northern California, reported a decline of 8%. In Shasta, all of that drop was at a single place, Shasta College, which is the only higher education in a 75-mile radius. Johnson of PPIC said it’s good news that the UC and CSU systems have fared relatively well so far, but the decline in community college enrollment could have knock-on effects a few years down the road. “If those students aren’t coming in as a front end, then we’re not going to see them in that transfer pool either,” Johnson said. Proof of concept Educators in Riverside County realized the need for the College Comeback program last summer after working with students like Ariel Jennings, who had just graduated from La Quinta High School near Palm Desert. The 19-year-old had been admitted to UC Riverside, but didn’t accept the school’s offer because she was unsure of how much financial aid she was getting. “I missed the deadline, like, twice,” she said. “And I didn’t understand financial aid or the paperwork or anything like that.” Jennings didn’t know where to turn. “At that point, we weren’t in school anymore so I couldn’t go to a high school counselor for help either,” she said. “My parents and I just felt really alone in the process.” Riverside County college going rates Riverside County saw a sharp decline in college-going seniors from 2019 to 2020, although community colleges bore most of that drop. She tried to contact UC Riverside herself, but “it’s really frustrating sending emails and then getting a reply two weeks later, and no one actually talking to you,” she said. The responses Jennings did get were vague, telling her to email other departments on campus. So she decided to enroll at College of the Desert, “since classes were going to be online anyway.” And then later in the summer, Jennings got a phone call. “I thought it was just one of those spam calls or something,” she said. “But I answered anyway.” The voice on the other end of the line was counselor Yuri Nava, who told Jennings she could help her. Nava explained Jennings’ financial aid award and told her it wasn’t too late to go to UC Riverside after all. Jennings was one of around 1,100 recent high school graduates from Riverside County who had been admitted to UC Riverside last year but had not accepted their offer or enrolled at another UC. County counselors and college admissions officers split the list and started reaching out in early July. Around 20 of those students who were contacted by the county ended up enrolling at UC Riverside, with several more getting help to go to community college. With the pandemic in full swing, last year’s admission season was confusing for colleges, students, and parents, said UC Riverside Associate Director of Undergraduate Admissions Alex Ruiz. He said the university worked with the county to increase outreach for what he characterized as an anomalous year, and that this year should be a return to relative normalcy. Last week, Jennings just finished her first year at UC Riverside as a political science major. “I’m a first generation [student], so the process was kind of hard, and I really needed the extra help that I got,” she said. Breaking the chainIn Riverside, Cifuentes hopes that College Comeback will show the need for ongoing postsecondary counseling that helps bridge the gap between the K-12 system and higher education. Her dream would be to have a designated counselor in each district who works with graduates. Alumni counselors are not a new concept; it’s a common position in private schools and some public charter schools like the Knowledge Is Power Program, or KIPP, network. “If I can show the impact of how many students we served, [the program] pays for itself” in terms of return for the community, she said. Since May, around 30 students have had appointments, but several others have gotten assistance via text and email. Cifeuntes expects the number to pick up as more alumni hear about the program. As for Cruz, he’s said he’s excited to start at Riverside City College this fall. He wants to study entrepreneurship and accounting so he can start his own business in the future. His mom, Rossy Elizabeth Diaz, is equally excited. She’s been encouraging Cruz to go back to school, and is looking forward to Cruz’ 16-year-old sister heading to college in a few years. Diaz appreciates the support Cruz got through College Comeback. “I feel really proud, really happy because I had my first kid when I was 17, so I didn’t have the chance to go to school,” she said. But “I had the chance to help them break that chain, for them to do something different from…their parents.” Source: Charlotte West Author - posted on CalMatters College News

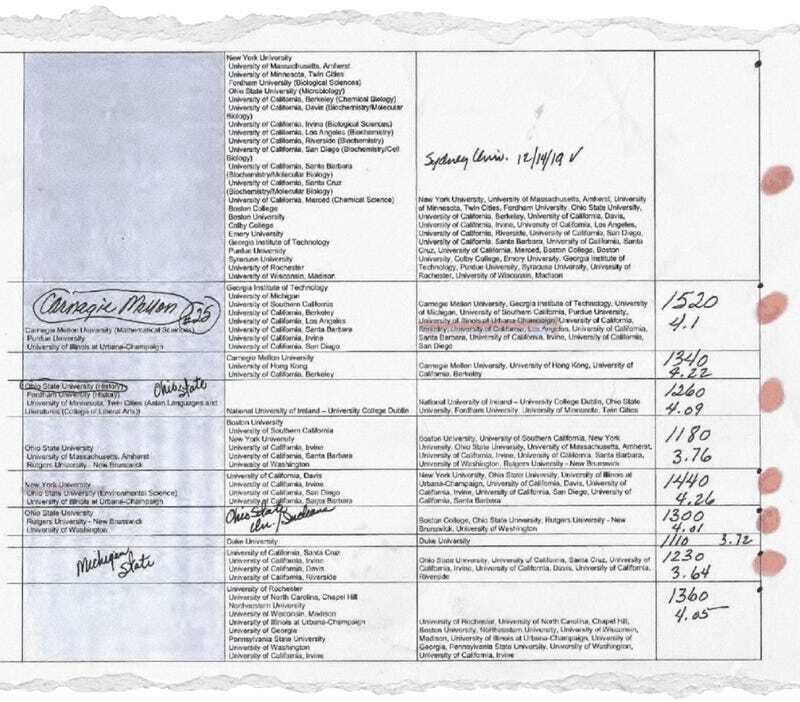

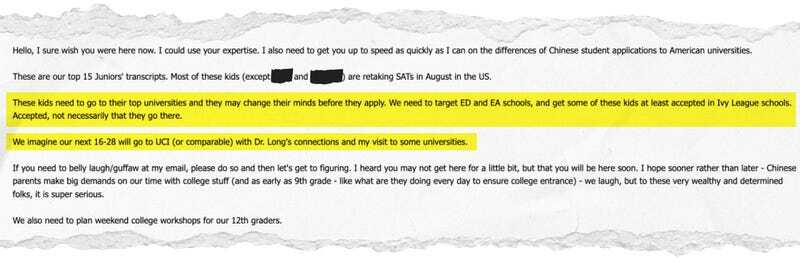

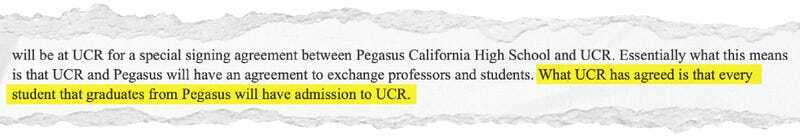

Photo by Nalani Hernandez-Melo for CalMatters The infamous 2019 Varsity Blues college-admissions scandal revealed that wealthy parents will do whatever it takes to ensure their children are admitted to elite colleges. Dozens of prominent parents — including the actress Lori Loughlin and her fashion designer husband, Mossimo Giannulli, as well as actress Felicity Huffman — took part in admissions counselor Rick Singer's criminal scheme to game the admissions system so that their kids could attend the University of Southern California, Yale, Georgetown, Stanford, UCLA, and other elite institutions. But Americans weren't the only targets — indeed, wealthy Chinese families were some of Singer's most lucrative clients involved in the scandal. As Varsity Blues grabbed headlines, though, Insider has learned of another scheme that, for years, quietly helped wealthy Chinese students seeking admission to top American colleges, particularly at the highly touted University of California system. An Insider investigation has found that admissions staffers at at least two University of California campuses — UC Irvine and UC Riverside — as well as a retired senior staffer within the UC Office of the President, the system's headquarters, worked with a swaggering businessman, Steven Ma, who sought a leg up for the students at his elite private high school in Qingdao, China. The help offered to Ma's students, records show, included specially tailored summer programs, a written pledge to work with students so they'd be competitive applicants for admission, special permission to apply even after the university deadline had passed, and — at least according to one local school official in California who worked closely with the Chinese school — guaranteed admission to UC Riverside for all graduates. One former California education official told Insider such an arrangement, if true, would be "appalling." Ma's school was called Pegasus California School, and it officially opened in 2016 based on the premise that — by mimicking the curriculum of a public high school in California — he could increase the chances that his wealthy Chinese students would gain admission to top U.S. colleges and universities. The school even guaranteed parents, in writing, that every graduate would gain admission to one of the top 100 US universities. Ma worked with some of the state's highest-ranking current and former education officials — Tom Torlakson, who at the time served as the state's superintendent of public instruction, and David Long, who previously served as state secretary of education before becoming the principal at Pegasus. With Torlakson and Long's help, Ma forged critical relationships with leading California universities and school districts to legitimize his operation — advertising to Chinese families that their children would be attending a school with a California curriculum. He also fostered a relationship with a struggling school district in Riverside County that issued official public school diplomas to his students. Ma worked to establish what he called a "favorable relationship" with UC Irvine and UC Riverside, both of which embraced the Chinese high school. That included paying a retired UC staffer who continued to work for UC Irvine as a contractor. Daniel Aldrich, a retired staffer for the UC Office of the President (as well as the son of UC Irvine's founding chancellor) worked for both UC Irvine and for Pegasus, Insider has learned. Records show that Aldrich contacted UC campuses on behalf of Pegasus, and he also supplied UC Irvine officials with a list of Pegasus students interested in attending the university, so those staffers could monitor the students' progress through the admissions cycle. One senior admissions staffer specifically told Aldrich that the students looked like competitive applicants for UCI. Aldrich communicated with UC personnel about Pegasus using his active University of California email address. Long told Insider that Pegasus paid Aldrich as a consultant. "Especially with international students and parents, it's helpful to have someone that has had or is connected with, previously or currently [with the University of California]. We try to stay away from the current, but he's a consultant so it's not that big of a [deal]," Long added. Aldrich confirmed to Insider that he was paid to consult for both UC Irvine and Pegasus, and that the high school also paid for him to travel to China. He said he never did anything improper in his work for Pegasus, which "produced quality students, and we look for quality students in the University of California." UC Irvine told Insider in a statement that Aldrich contacted the university to see if Pegasus students' applications were missing transcripts or other necessary documents, and never discussed admissions. "I'm not an expert in education" Beyond Aldrich, Pegasus was close to UC Irvine in other ways. The university hosted an annual three- to four-week summer program specifically tailored to Pegasus students, and sent representatives to the school's China campus to meet with students and parents. And in an interview, a former Pegasus headmaster told Insider that Long said that UC Irvine pledged to accept at least some Pegasus graduates. "Dave Long always spoke about his connections with UC Irvine and with the president there," Allen Riedel, the former headmaster, told Insider. "[He] told us...if they wanted to, they could go directly to UC Irvine no problem." When asked to clarify, Riedel said: "Dave Long reported that to me that they wouldn't take all of our students but they would take some of them." Long denied that he ever made that statement. "I don't even know the president," he said. "And about a statement to say if you just come from Pegasus you can get in automatically, that's not correct. You have to reach the minimums to even be considered." Yet, in an August 2018 email obtained by Insider, Riedel explicitly invoked "Dr. Long's connections" as he pressured the school's guidance counselor to meet admissions goals: "These kids need to go to their top universities," he said. "We need to...get some of these kids at least accepted in Ivy League schools. Accepted, not necessarily that they go there. We imagine our next 16-28 will go to UCI (or comparable) with Dr. Long's connections and my visit to some universities." Ma acknowledged that Pegasus worked to establish what he called "a favorable relationship" with both UC Irvine and UC Riverside. But he insisted that the goal was to help "bring educational insight to Pegasus California School students" rather than secure them a leg up in admissions, which he said would be "impossible" anyway. Asked why Long might say that his connections could help Pegasus students applying to UC Irvine, Ma replied: "I don't know. I'm not an expert in education."In a statement UCI said it never guaranteed admission to anyone. "According to the news this Pegasus school reports, the student from this school can get privileges when they apply to UCR"At UC Riverside, the favorable relationship that Ma described seemed especially obvious. During a May 2019 school board meeting for the Val Verde Unified School District, a Southern California school district that developed a close relationship with Pegasus, the district's superintendent, Michael McCormick, went so far as to publicly proclaim that UC Riverside guaranteed admission to all Pegasus graduates, according to the minutes of a public-school board meeting. "Essentially what this means," he explained, according to public meeting minutes, "is that UCR and Pegasus will have an agreement to exchange professors and students. What UCR has agreed is that every student that graduates from Pegasus will have admission to UCR." "The goal of public education in the state of California is to support California children, and higher education does allow [students] from other countries, but we don't guarantee them admission," said Delaine Eastin, who served as California's state superintendent of public instruction in the 1990s and early 2000s. "I find it appalling if it is true that UC Riverside has guaranteed admission for these graduates." In a statement, a spokesperson for UC Riverside said McCormick was mistaken. "It appears that an individual made some incorrect statements at a Val Verde school board meeting, about which statements the University had no knowledge until they were later brought to the university's attention." According to records obtained by Insider, UC Riverside admissions staffers also offered Pegasus students the opportunity to submit late admissions applications to the university, giving them an advantage over students who abided by the UC-wide November 30 deadline.

In December 2018, Long sent the school a list of 18 late Pegasus applicants who wanted to apply to UC Riverside. Emails show that the university's interim associate vice chancellor of enrollment services personally authorized a late application through December 15 — giving Pegasus students an extra 15 days to apply. The spokesperson for UC Riverside said that of the 18 applicants sent to the school, 13 had actually already applied on time, and that none of the remaining five ended up submitting late application appeals. Both Ma and Long said that it was not uncommon for students to apply to universities after the admissions deadline. At least one prospective Pegasus student, however, was confused by the high school's arrangement with UC Riverside. A Chinese student living outside of Qingdao contacted the university and expressed interest in transferring to Pegasus. she had read online about an official cooperation between the college and high school, and was under the impression that being at Pegasus would bolster her chances of being accepted to UC Riverside. She wanted to know if what she read was true. "According to the news this Pegasus school reports, the student from this school can get privileges when they apply to UCR," she said. "If it is true, I am considering to transfer into this Pegasus school to get the priority offer from UCR." Source: Nicole Einbinder - Investigative Reporter of Insider. Photo: Taken by Christopher Vu and Samantha Lee Nursing is the only health profession with multiple pathways to entry-level practice. Two of these pathways are the Associate Degree in Nursing (ADN) and Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) programs. Although graduates from both programs take the same licensure exam — the NCLEX — BSN programs include additional courses supporting the further development of nursing knowledge, skill and clinical judgement.

With this in mind, Southern State Community College (SSCC) and the University of Cincinnati (UC) College of Nursing are signing a dual-admission agreement that will allow nursing graduates to seamlessly transition to UC’s RN to BSN Online Program. Students applying to SSCC’s ADN program have the choice to simultaneously apply to the RN to BSN program and have their application and confirmation fees waived by UC. These students will be able to access UC resources and support while pursuing their degree at SSCC. “We are excited to offer this opportunity and partner with Southern State to increase the number of BSN-prepared nurses in the Adams County region,” said Rebecca Lee, Ph.D., director of the RN to BSN program at UC. The UC College of Nursing has offered its RN to BSN program for more than 20 years. In addition to its widely recognized reputation, the program offers the flexibility working nurses need as they pursue their BSN, be it by requiring only nine core nursing courses to graduate, by offering an adjustable schedule with six start dates per year or by providing course load flexibility so students can choose to pursue full-time or part-time options. An accredited program, UC’s RN to BSN program allows its graduates to progress to graduate education, if they choose to do so. The Associate Degree Nursing Program at Southern State has been preparing nurses to serve the community for 35 years. Students may enter the ADN Program in the traditional pathway of four semesters or as a licensed practical nurse in the transition pathway and complete in 12 months. These can be the first steps to obtaining a BSN in nursing practice and offers the students opportunities to identify the best pathway for them. “We look forward to the success of our graduates as they easily access this pathway to expand their nursing education which will positively impact the care they provide our community,” said Dr. Julianne Krebs, SSCC director of nursing. The official, virtual signing of the partnership will take place at 9 a.m. June 24. Source: The Times - Bazettle Legislature also seeks to reduce out-of-state students enrolling at three UC campuses and increase in-state students California’s financial aid programs would be expanded, and fewer out-of-state students would be able to attend the University of California, under a budget proposal announced Tuesday by state legislators.

The budget agreement reached by state Assembly and Senate leaders, which must still be negotiated with Gov. Gavin Newsom, also calls for hiring more faculty at the state’s community colleges, increasing overall enrollment at both UC and California State University and eliminating Calbright, the state’s online-only community college. The full Assembly and Senate also must still vote on the budget and approve it by June 15. Lawmakers can then negotiate with Newsom through June 30. Lawmakers supported many of Newsom’s major higher education plans included in his latest budget proposal, such as increasing funding for the two university systems and restoring cuts that were made at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic last year to the systems. They also agreed to pay down all deferrals, also known as late payments that are essentially IOUs, at the state’s community colleges. Lawmakers and Newsom have also agreed to pay down deferrals at K-12 school districts. In some other areas, however, legislators modified or rejected Newsom’s proposals, or put forth new proposals of their own, triggering the need to negotiate with Newsom for them to be included in the final state budget. Financial aid The Legislature’s proposal would make more students eligible for Cal Grants, the state-funded financial aid awards, and also increase the amount of some of those awards. Under the Legislature’s plan, there would be no age or time out of high school requirements for students to be eligible for Cal Grants. Under the current system, to be guaranteed a Cal Grant, incoming first-year students must be one year or less removed from graduating from high school. Transfer students must be under the age of 28. The change is aimed at expanding the Cal Grants to older adults who may be returning to college or entering college later than the average student. By providing $488 million to end those age barriers, lawmakers estimate that an additional 133,000 community college students would become eligible and another 40,000 CSU and UC students would also be newly eligible. The changes would go into effect during the 2021-22 academic year for community college students and in 2022-23 for UC and CSU students. On top of that, the Legislature proposed to allocate another $125 million to increase the amount of the Cal Grant B award from about $1,600 to $2,000 by 2022-23. Those grants help students cover non-tuition expenses like housing and books. The Legislature also proposed spending $542 million to expand the state’s Middle Class Scholarship, making Cal Grant recipients eligible for those awards to help pay for non-tuition costs. Currently, those scholarships are not available to students who receive Cal Grants. The expansion would go into effect in 2022-23. University of California The Legislature’s budget agreement seeks to reduce out-of-state enrollment at the University of California while increasing the number of in-state students who enroll. The proposal by lawmakers would provide $31 million annually starting in 2022-23, $61 million in 2023-24 and $92 million in 2024-25 to reduce the enrollment of out-of-state and international students at UC Berkeley, UCLA and UC San Diego. The plan calls for those campuses to reduce their overall undergraduate enrollments of nonresident students to 18% over five years. Currently, nonresident students make up 23.5%, 22.5% and 22.1% of undergraduate enrollment at UC Berkeley, UCLA and UC San Diego, respectively. The plan would create spots for 900 more California residents every year at those campuses, according to the Legislature’s estimate. “We think that’s a top priority because those are the three most desirable campuses,” Assembly Budget Committee Chairman Phil Ting, D-San Francisco, said during a news conference Tuesday. That proposal is less ambitious than a plan introduced by the Senate last month that would have forced those campuses and the entire system to cap enrollment of out-of-state students among incoming freshmen at 10% by 2033-34. However, the Legislature also proposed allocating $67.8 million to increase in-state enrollment at UC by 6,230 students in 2022-23. Lawmakers also rejected Newsom’s proposal to make UC’s base funding contingent on increasing online course offerings and creating a dual admissions guarantee for community college freshmen seeking to transfer to a UC campus. California State University Lawmakers approved a slightly modified version of Newsom’s proposal to convert Humboldt State University into the CSU system’s third polytechnic institution. The Legislature proposed spending $25 million annually to support that conversion, as did Newsom. But while the governor proposed spending $433 million in one-time money to support that project, lawmakers offered $313 million in one-time spending. Lawmakers also proposed $81 million in ongoing funding to increase undergraduate enrollment at CSU by 9,434 new students in 2022-23. The Legislature’s plan also includes $50 million in one-time dollars for CSU to expand teacher preparation programs over the next five years. Like with UC, lawmakers rejected Newsom’s proposal to make CSU’s base funding contingent on it increasing the number of online classes offered and creating a dual admission guarantee. Community colleges As expected, lawmakers are proposing to eliminate Calbright, the online-only community college, which opened in October 2019. What’s unclear is whether Newsom will get on board with doing away with the college. The Legislature pushed last year to close the embattled college, but it ultimately survived. The Legislature also proposed just $15 million in one-time funding to expand zero-cost textbook degrees across the community colleges, far less than the $115 million the governor proposed. In the budget proposal, Assembly staff called Newsom’s proposal “worthwhile” but said there is “no justification” for that “significant funding level.” Lawmakers propose spending $170 million in ongoing funding to hire at least 2,000 more full-time faculty across the community college system and another $75 million to support part-time faculty. Student housing The Legislature’s proposal modifies Newsom’s plan to spend $4 billion in one-time funding, split between 2021-22 and 2022-23, to create a housing grant program that would expand affordable housing across the state. Instead, lawmakers offered to create a $4 billion fund that could be used to build housing at the state’s public colleges and universities but could also go toward other projects, like building new campus facilities or expanding existing ones, said Sen. Nancy Skinner, D-Berkeley, chair of the Senate’s budget committee. Source: EdSource HIGHLIGHTING STRATEGIES FOR STUDENT SUCCESS “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do?”

That quote, which has been wrongly attributed to John Maynard Keynes, speaks to intellectual honesty that’s all too rare these days. On the left and the right, it’s more likely to be “When the facts change, I double down. What are you going to do about it?” That was evident in the decision by the University of California to end standardized testing as a criterion for admission to its nine undergraduate campuses. UC has gone further than other universities in not just making test scores optional for admission, but not considering them at all. The decision, however, came after an exhaustive 228-page report last year by a panel of UC academics commissioned by then-President Janet Napolitano to examine whether standardized tests like the SAT and ACT are equitable and indicate college readiness. Conventional wisdom holds that standardized tests are biased toward the wealthy and don’t have much predictive value. Some even call them racist because Black and Latino students’ test scores have consistently lagged behind those of whites and especially Asians. But the task force — co-chaired by eminent Black and Latino professors — spent months poring through data and interviewing statisticians, admissions directors and others, and found that standardized tests were good predictors of future academic performance, as good as or better than high-school grade point average (GPA). They also helped thousands of applicants from underrepresented minorities get into UC who wouldn’t have been accepted using GPA alone. Grades vs. standardized tests “Overall, both grades and admissions test scores are moderate predictors of college GPA at UC,” the report said. “The predictive power of test scores has gone up, and the predictive power of high school grades has gone down,” probably because of grade inflation in high school. Students who had high test scores also had high graduation rates, but “the lowest-scoring students typically do not perform well at UC. … At UC, each of the primary success measures is clearly correlated with, and predicted by, scores on standard college admissions tests,” the report found. And not just for wealthy kids, either. “Test scores contribute significant predictive power across all income levels, ethnic groups … and across all campuses and majors,” the report said. “We found that test scores were better predictors of outcomes for underrepresented groups than for majority groups.” Plus, standardized test scores, which were part of UC’s multi-factor admissions process, increased diversity at some of America’s leading public universities. ”Admission tests find talented students who do not stand out in terms of high school grades alone,” the report found. “The SAT allows many disadvantaged students to gain guarantees of admission to UC.” Low-income students How many? Some 22,613 students were admitted to UC campuses from 2010 to 2012 (the period it studied to trace full college outcomes) based on a formula that included test scores who wouldn’t have gotten in by GPA alone. Of those, 25% were members of underrepresented minority groups and 47% came from low-income families, or more than 5,000 and 10,000 additional students, respectively. The report, which passed the Assembly of the Academic Senate by 51-0, also was endorsed strongly by UC’s admissions directors. But anti-test advocacy groups were unmoved and other stakeholders who were convinced tests were inequitable or racist held their ground. In May 2020, outgoing President Napolitano, who had previously served as Secretary of Homeland Security in the Obama administration, recommended dropping standardized tests in UC admissions. The UC Board of Regents voted to eliminate the tests as admissions requirements starting in 2023. A recent settlement of a lawsuit accelerated that timeline, so the nine UC campuses will no longer consider standardized tests in undergraduate admissions. UC declined to provide someone to interview by deadline. ‘Ship has sailed’ The two co-chairs of the task force had mixed feelings. “I’m comfortable, I’m not looking back. I think the ship has sailed and you see us moving on,” said Dr. Eddie Comeaux, a professor at UC Riverside. He said the evidence points to continuing inequities in admissions. “There are decades of research that speak to the structural barrier to standardized tests, specifically the correlation to wealth,” he said. “These students who have historically been excluded saw tests as a barrier,” even though the report found that low GPA in required courses was a bigger obstacle to admissions to UC than test scores for underrepresented students. This year, when the test requirement ended, UC campuses got a staggering 203,700 applications for freshman admission, 32,000 more than the previous year. And, like other colleges and universities across the country, UC saw a significant rise in applications from Black and Latino students, which will likely result in a somewhat more diverse freshman class. Still, Comeaux agreed with the report’s finding that “roughly 75% of the opportunity gap arises from factors rooted in systemic racial and class inequalities that precede admission: lower high school graduation rates … lower rates of [course] completion … and lower application rates.” “And there is structural racism in our educational system where we have a separation of the have and have not,” Comeaux said, but he stopped short of calling the tests themselves racist. ‘Public appeasement’ “There are a lot of barriers upfront, then, how can you be prepared for any standardized tests? The cards are stacked against you,” the other co-chair, Dr. Henry Sanchez, a pathologist who teaches at the UCSF School of Medicine, told me. But, he added, “if you have all these barriers put in over decades, do you think you’re going to change it by one law? One change in policy?” “Are you doing this for public appeasement or really getting at the underlying core issues?” Sanchez continued. “If you get rid of the test, now what? You’ve got to consider the impact for not just this class, but a generation of children going through public education. Are they going to be prepared for what society wants and needs?” The pandemic has prompted a massive experiment with standardized testing in higher education. We may not know for a few years whether students who didn’t submit test scores but were admitted to colleges and universities will succeed there. But based on what happened at UC, don’t expect people to change their minds if the facts change. That ship sailed long ago. Source: Howard Gold - is a MarketWatch columnist who writes regularly about college admissions. RELATED ARTICLE: California public universities abandon standardized tests, other schools ditch ‘test optional’ California public universities abandon standardized tests, other schools ditch ‘test optional’6/9/2021 ‘Test blind’ is the UC’s name for new reform

The Board of Regents at the University of California system voted on May 21 to make all of their schools “test blind” for the 2023-24 school year, and to not use the SAT or ACT standardized tests after that. The UC website reported this suspension will “allow the University to create a new test that better aligns with the content the University expects students to have mastered for college readiness. However, if a new test does not meet specified criteria in time for fall 2025 admission, UC will eliminate the standardized testing requirement for California students.” The UC system had been one of many college systems in the country that went temporarily “test optional” in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Whether or not standardized tests come back at those other schools is currently up for grabs. Long seen as a metric for academic success and aptitude, standardized testing has come under increased scrutiny in recent years by some educators and activists. The worldwide pandemic at least temporarily tipped things in their favor. The anti-ACT/SAT group FairTest sent out a news release in early May announcing, “The number of accredited, bachelor-degree granting colleges and universities that will not require current high school juniors applying for fall 2022 admission to submit test scores has topped 1,400 schools. That’s more than 60% of the 2,330 undergraduate institutions in the United States.” The group’s executive director Bob Schaeffer celebrated the results. “Last year’s sharp spike of admissions exam suspensions was not a one-time phenomenon. Schools that waived ACT/SAT score requirements during the pandemic generally saw more applicants, better academically qualified academics, and more diversity of all sorts. Now, most are extending those policies for at least another year,” he said in the news release. The usefulness of tests But whether or not many more schools will follow the UC example remains to be seen, and is complicated by the fact that the UC regents went against the recommendation of a task force assembled by the Academic Senate of the UC to go test blind. In its final report, the task force went out of its way to say what it did not recommend. These not to do items included, “The Task Force does not recommend that UC make standardized tests optional for applicants at this time,” and “The Task Force does not recommend adopting the Smarter Balanced Assessment in lieu of currently used standardized tests.” The stated reasoning behind that was the SAT/ACT’s diagnostic effectiveness. The task force “found that standardized test scores aid in predicting important aspects of student success, including undergraduate grade point average, retention, and completion.” Moreover, the UC task force found that the tests had actually become better over time at predicting these things than other data from California high schools, because of such things as “grade inflation.” Their findings affirmed research by St. Mary’s College economist Samuel Rohr that a “higher aggregate score on the SAT helped predict the retention of science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and business students.” “For every point increase in SAT, there was 0.3% increase in retention,” Rohr reported in the Journal of College Student Retention. More recently, a researcher looked at what happens to schools when you remove the tests, and discovered less than impressive results. In a study of nearly 100 test optional schools published in April in the American Educational Research Journal, Vanderbilt education policy PhD candidate Christopher Bennett reported, “I do not find clear overall evidence of an increase in applications, though there may have been a short-term rise during the first few years of the policy.” When reach schools exceed grasp There’s an additional wrinkle that may affect graduation rates and future earnings of students who are now able to get into schools they would have considered a “reach” in the past. Different colleges and universities have different levels of difficulty. Struggling students often downshift their majors from more highly remunerative STEM degrees to easier subject matter, which can have life-long effects. “Admitting students with lower SAT scores to fulfill diversity quotas may prevent those students from achieving their academic and career goals—something they might have done at a lower-tier school,” wrote James Piereson and Naomi Schaefer Riley in a column for City Journal. “At the most elite schools, the likelihood is that students who didn’t perform as well as their peers on the SATs will simply be shunted into easier but less remunerative majors. For schools farther down on the academic ladder, these efforts could mean lower overall graduation rates,” Piereson and Riley argued. Back to the test Even with the recent shift against standardized testing at some schools, the debate is far from over. Witness what happened in Georgia’s counterpart to the UC system, the University System of Georgia. The Georgia board of regents voted in May to make “test optional” into a one-year-only experiment. Most of those prospective students who apply next spring to Georgia public universities must submit either ACT or SAT test results. The prospect of a return to testing normalcy appeared to anger FairTest’s Schaeffer. “The politically appointed University System of Georgia Board of Regents, most of whom are not educators, are bucking a strong national trend by refusing to extend ACT/SAT optional policies for at least another year,” he told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Source: The College Fix RELATED ARTICLE: Opinion: Standardized tests increased minority admissions in California, but state universities dropped them anyway After a public outcry over massive rejections by University of California schools this year, state lawmakers hope to increase the number of in-state students accepted by the system.

The population of the UC system has increased the number of students from out of state to about 18%. Some lawmakers are pushing to reduce that number to 10%, making more room for California students - but that would also decrease tuition revenue to the system. "It's so important because Californians should get the first shot to attend the University of California," said Assemblyman Phil Ting, D-San Francisco, who chairs the Assembly's budget committee. "Unfortunately over the last 10 to 15 years, because of the last great recession, we've seen a huge jump in out-of state student enrollment," Ting added. "What we want to make sure is we're making more room for Californians because they've been crowded out by out-of-state students over the last 10 years." But with out-of-staters paying close to three times as much in tuition, there's the question of how the UC system will make up for this loss in income. UC officials say they understand the goal, but it could lead to negative financial consequences for the system. "We understand and support the Legislature's goal of providing more opportunities for Californians at UC, though we believe trying to achieve this through reducing nonresident students will potentially lead to unanticipated outcomes," the UC system said. Ting says there's a simple answer: The state will have to make up the difference. "We're going to have to give more state funding, that's the bottom line," Ting said. "And I think the state is very much in favor of that." The plan could be approved as part of the state budget by the middle of next month. If it becomes law, it would take effect in the fall of 2022. Source: Los Angeles and Southern California News, Weather, Traffic - ABC7 KABC A bold plan for UC: Cut share of out-of-state students by half amid huge California demand5/31/2021 As the University of California confronts record demand for admission, lawmakers are considering a plan to cut in half the share of nonresident students to make more room for locals. As the University of California faces huge demand for seats — and public outcry over massive rejections by top campuses in a record application year — state lawmakers are considering a plan to slash the share of out-of-state and international students to make room for more local residents.

The state Senate has unveiled a proposal to reduce the proportion of nonresident incoming freshmen to 10% from the current systemwide average of 19% over the next decade beginning in 2022 and compensate UC for the lost income from higher out-of-state tuition. This would ultimately allow nearly 4,600 more California students to secure freshmen seats each year, with the biggest gains expected at UCLA, UC Berkeley and UC San Diego. The share of nonresidents at those campuses surpasses the systemwide average, amounting to a quarter of incoming freshmen. UC, however is pushing back, saying the plan would limit its financial flexibility to raise needed revenue and weaken the benefits of a geographically broad student body. “It’s not about ending out-of-state students — they really add to the mix and the educational experience,” said Sen. John Laird (D-Santa Cruz), whose Senate budget subcommittee on education discussed the plan this month. “We just have to make sure there’s enough spaces for in-state students.” The question of who should get a coveted seat in the nation’s premier public research university system has raged for years, as legislators are perennially pummeled by constituent complaints about UC access. The issue has ignited political fireworks, a scathing state audit, UC admission reforms and extensive policy work into how to accommodate the growing number of qualified California applicants amid limited funding and space. Although the UC system is constitutionally autonomous and controls its own enrollment decisions, state lawmakers have used their power over purse strings to compel UC to adopt their directives. Under political pressure, the UC regents in 2017 capped nonresident enrollment at 18% systemwide, with a higher share grandfathered in for UCLA, Berkeley, San Diego and Irvine. But some legislators are saying that cap is still too high — and that this is an opportune year to begin driving it down because Gov. Gavin Newsom has proposed using some of the state’s record $75 billion surplus to give UC $805 million, which university leaders have applauded as the largest investment in the university system’s 153-year history. But Newsom has not tied that funding to increases in California student enrollment, as previous state budgets have done, and UC’s 2021-22 budget plan doesn’t include higher targets. The Senate 10% plan is the first volley in what is bound to be protracted negotiations over the issue before the June 15 deadline for legislative passage of the budget. “We’re giving them a blank check and they’re giving us nothing in return for our priorities,” said Assemblyman Kevin McCarty (D-Sacramento), whose budget subcommittee also has long pushed for more California students. “When we go to our districts and talk to our constituents, access to the University of California is a front and center issue that we hear about.” UC officials say they share the goal of enrolling and graduating more California students and have added 19,000 more of them since 2015. But they oppose the 10% plan, saying nonresidents enrich the college environment for all students and pay more than $1 billion annually in supplemental tuition that helps fill budget holes. That revenue, officials say, has allowed UC to enroll more Californians not fully covered by state funding, as well as provide more faculty, staff, student services, financial aid and campus facility upgrades. “We understand and support the Legislature’s goal of providing more opportunities for Californians at UC, though we believe trying to achieve this through reducing nonresident students will potentially lead to unanticipated outcomes,” the university said in a statement. UC called for a “stable and predictable revenue source” to increase California undergraduate enrollment without hurting low-income students or limiting efforts to recruit students outside the state. For thousands of California families, however, the increasing difficulty of accessing a UC seat at many campuses after they’ve supported the university system with their taxes for years has fueled heartbreak, frustration and anger. And high school teachers and counselors want to see more of their hard-working students reap the rewards of a UC acceptance letter. “We have the great privilege of having these extremely prestigious public universities in the state but the downside is they’re really popular and everyone is trying to get in,” said Heather Brown, college counselor at Los Angeles High. “It’s only fair that students of residents who have been putting tax dollars into the pot should benefit.” Weni Wilson, a San Marino parent, said the high-performing children of several of her friends did not get admitted to their top UC choices this year and the topic is so painful they’ve had to agree not to talk about college admissions in order to continue their social gatherings. Wilson said her own daughter will attend UC Irvine this fall, but she supports the Senate plan as a way to open more access to other California students — including her two younger children who will be applying to college in five years. “As a California taxpayer, I would expect and hope that the children of California residents have the opportunity to attend UC schools because right now the opportunity is taken away for a lot of these kids,” Wilson said. The controversy began in the wake of the 2008 recession, when UC sought to offset major state budget cuts by aggressively recruiting and admitting more nonresident students, who each pay an additional $29,000 in tuition a year. As a result, the share of nonresident undergraduates systemwide tripled from 5% in 2007 to 15% in 2015. In 2016, a state audit found that campuses harmed local students by admitting too many nonresidents. In a fiery response, then-President Janet Napolitano called the findings “unfair and unwarranted.” But UC regents, following an audit recommendation, approved the 18% cap. State lawmakers, however, pressed for more changes — directing UC to develop a plan beginning in fall 2020 to gradually reduce nonresident students to 10%, but it was not implemented. Now, in a record-shattering year of more than 200,000 applicants vying for 46,000 freshman seats, the state Senate has made the enrollment issue one of its top educational priorities, Laird said. Under the 10% plan, the share of nonresident students would be cut at UCLA, Berkeley, San Diego, Davis, Irvine and Santa Barbara but allowed to rise to that level at Santa Cruz, Riverside and Merced. The plan would replace the lost tuition from nonresidents and cover the cost of additional California students to take their spots, beginning with $56 million next year and growing to $775 million by 2033. Seija Virtanen, UC associate director of state budget relations, told Laird’s subcommittee that it would be more cost-effective to fund more California undergraduates, whom the state funds at roughly $10,000 each, than cut the number of nonresidents and backfill their lost tuition at more than twice that amount. She also said the Senate plan could create a “financial vulnerability” for UC — if state funding were cut again, for instance, in another recession. UC student leaders also have spoken out against the 10% plan. Aidan Arasasingham, president of the UC Student Assn., said students from other states and countries bring a vibrant diversity to campus and their talent and skills to California since most stay here and work after graduation. “You can’t have a globally minded education without learning from peers from across the state, the country and world,” Arasasingham said. “Instead of building walls to keep certain students out, we need to build stronger bridges of opportunity for California residents to allow them to come here through increased access, more retention or the funding of new seats at UC.” Even some supporters of the plan have some qualms. “If the state isn’t able to fully compensate UC for the lost income from out-of-state tuition, are they going to have a higher ratio of students to professors? Are they going to have crumbling infrastructure?” Wilson asked. “Is it worth it to allow more kids in but then have a poor quality education?” Assemblyman Phil Ting (D-San Francisco), who chairs the Assembly budget committee, said nonresidents made up only 5% of Berkeley students when he attended that campus three decades ago and returning to lower levels was “long overdue” — especially at the most highly sought after campuses. UCLA and Berkeley, he said, can’t significantly add more Californians without reducing nonresidents because they are at capacity with little physical room to grow. At a February subcommittee hearing, Ting pressed UC President Michael V. Drake on whether UC should lower the 18% cap. “It’s a complicated question,” Drake replied, adding he would be happy to work with legislators to find the right balance. The Assembly also has supported the 10% plan and plans to flesh out details of its own UC proposal in the next several days. “We have so many residents who are dying to go to UC and we want to give as many UC eligible students the opportunity to come to the University of California as possible,” Ting said. Source: The San Diego Union Tribune The regents of the University of California spoke as one when they unanimously scrapped the Scholastic Aptitude Test in a virtual meeting last month. “I believe the test is a racist test,” said one regent, Jonathan Sures. “There’s no two ways about it.”

But the regents’ decision flouted a unanimous faculty-senate vote a few weeks earlier to retain the SAT for now, after a yearlong study by a task force found the test neither “racist” nor discriminatory and not an obstacle to minorities in any way. The 228-page report, loaded with hundreds of displays of data from the UC’s various admissions departments, found that the SAT and a commonly used alternative test, ACT (also eliminated), helped increase black, Hispanic and Native-American enrollment at the system’s 10 campuses. “To sum up,” the task force report determined, “the SAT allows many disadvantaged students to gain guaranteed admission to UC.” So how could the liberal governing board of a major university system reject the imprimatur of its own liberal faculty researchers and kill a diversity accelerator in the name of the very diversity desired? The answer: The urgency of political momentum against the tests proved irresistible and swept away the research and data. Standardized tests were created about 100 years ago by what became the College Board to provide qualified Jews, Italians, Irish and others a better chance of getting into elite institutions dominated at the time by privileged, well-connected, mostly Protestant families. The idea was that the test created a national standard by which all students from all parts of the country and backgrounds could be compared. But over the years some minority groups have scored significantly lower on the test than others. This has led many educators, civil rights activists and some academics to argue that the tests are racially biased obstacles to the goals of opportunity and diversity. They say the tests favor affluent families, most of them white, who are able to pay for things like private tutoring and summer enrichment programs of the sort that are out of reach for poorer families. This was the prevailing view among the UC regents. The debate, far from new, is complicated and something of a scholarly maze with numerous research studies seeming to support one or another side of the question. But there was little ambiguity in the findings of the rebuffed UC faculty task force — scholars from different fields who in almost any context would be considered solidly liberal and who studied the SAT specifically as it is used in the University of California system. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed