|

A recent FairTest tally finds that more than 1,600 four-year schools will not require students to submit ACT/SAT scores to be considered for fall 2022 enrollment. Therefore, more than two-thirds of the 2,330 bachelor-degree institutions in the U.S. should have in place admissions policies which are generally regarded as more inclusive to minority students, including multilingual learners. The list of ACT/SAT-optional and test-blind schools (https://fairtest.org/university/optional) is made available by the National Center for Fair and Open Testing (FairTest). The organization has been at the forefront of the U.S. test-optional admissions movement since the late 1980s. “The coming year’s high school seniors should take advantage of the full range of admissions options,” explained FairTest executive director Bob Schaeffer. “Nearly all the most competitive liberal arts colleges in the country will not require ACT/SAT scores from applicants for fall 2022 seats. Similar policies will also be in place at a majority of public university campuses.” “Study after study—the most recent from the University of California—has shown that eliminating admissions test requirements enhances undergraduate diversity without reducing academic quality,” Schaeffer concluded. “FairTest expects the number of test-optional institutions to continue growing because the policy is a ‘win– win’ for both students and schools.” The UC system announced in July that for fall 2021, without using SAT or ACT scores in admissions, “students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups comprise 43% of admitted California freshmen, the highest proportion of an incoming undergraduate class and the greatest number in UC history at 36,462.” The major exceptions to the strong test-optional trend, according to FairTest, are public college systems in Deep South states such as Georgia and Florida, U.S. service academies, and some small religious colleges Source: Language Magazine Improving Literacy & Communication

0 Comments

High school seniors rethink taking SAT and ACT tests as colleges modify admission processes9/26/2021 For decades, standardized test scores have been a key benchmark in college admissions decisions. But now, high school students must decide whether they should invest the study time and money in taking the SAT and ACT exams or potentially miss out on a way to shine among applicants. While there has been discussion for some time over the fairness of using the standardized tests in the admissions process, the need to not gather students together in testing rooms during the pandemic made eliminating their use last year a simple decision for most in higher education. The UC and Cal State systems recently announced they will continue to disregard standardized test scores in admissions or scholarship decisions, but many private schools say they have made submitting scores optional. This gray area in the admissions process has left many high schoolers confused about whether they should take the exams. For Orange High School senior Melissa Medina, who is mainly applying to UC and Cal State schools, the decision wasn’t too difficult. The colleges she’s aiming for won’t consider her scores even if she took the exams. “When I heard schools were keeping things test-optional, I was relieved,” Medina said. “I’ve always thought that standardized testing limits the potential of many students, and it places labels on them. Just because you aren’t a good test taker doesn’t mean you’re not capable of doing more.” But the decision isn’t so easy for those interested in private or out-of-state colleges. When universities say they’re “test-optional,” do they really mean it? If schools are using scores if they get them to evaluate applications, there’s still pressure to take the exams and keep open options for their future education, students said. The SAT has long been criticized because studies indicate test-takers from wealthier families tend to score higher. Opponents of the test have called it “discriminatory,” saying the success of students from higher-income backgrounds stems from their ability to pay for test preparation programs – something many low-income families can’t afford to do. Applying to colleges can already be pricey. It costs $55 to register for the SAT and $85 to take the ACT with writing. On top of that, the average college application fee is $43; schools in the UCs system charge $70 per school. Stanford University charges applicants $90. So if a student were to apply to five colleges and take either the SAT or ACT once, they would be looking at hundreds of dollars in fees. And once they get into a school, tuition isn’t cheap. The test-optional movement started when the pandemic first hit. High schoolers had nowhere to take the exams when schools, many of which doubled as testing centers, shut down in March 2020. The tests weren’t adapted to an at-home format, so many of last year’s high school seniors just skipped them. Some traveled to states with fewer restrictions to take the tests, but they were in the minority. Most testing centers reopened in early 2021 for this year’s seniors – allowing them several dates to sit for the SAT or ACT before most private college applications are due in January. They’ll have to choose whether they’ll take the exams or send in applications without scores. Medina said she initially planned to rent a book to study with until she heard providing scores would be optional. Now, she uses her study time to focus more on community volunteering and writing her personal essays. “Now that I don’t have to worry about test scores, I can really just show who I am. I can show what kind of student I am in other areas,” she said. “That says much more than just a score.” But, Orange Lutheran High School senior Adam Hewitt was bummed the public California colleges aren’t considering standardized test scores in their admission decisions. Hewitt earned a near-perfect score on the ACT. Though he’s happy with his GPA, he said “it’s not as high as some other kids’” and was hoping to make up for it with his ACT score. “I feel like I’ve kind of been at a disadvantage for that, but I also completely understand why it’s optional. I fully support it,” Hewitt said. “Because I have friends who I know could do well on it and they weren’t able even to take it.” What colleges are saying Standardized tests are such a huge part of admissions culture that it feels strange to not have to study for them anymore, Medina said. Some of her friends still plan to take the SAT or ACT to see if they do well, she said. If they get a score they’re happy with, they’ll submit it to boost their chances; if they do poorly, they won’t. But for UC hopefuls, this strategy won’t work. Scores will not be looked at when evaluating applications, UC Irvine Executive Director of Admissions Dale Leaman said. “We don’t see their scores at all – no matter what they do or what they’ve taken – when we make our admissions decision,” Leaman said. “The only time you would see those scores is down the line after they’ve accepted our offer of admission.” SAT and ACT scores may still be used to place students in classes or to satisfy general education requirements, Leaman said. The Cal State system has suspended the use of SAT and ACT scores for making admissions decisions until at least fall 2023, spokeswoman Toni Molle said. It may also use scores to place enrolled students in courses. “The CSU is currently evaluating the future use of standardized test scores in first-time freshman admissions with internal and external stakeholders,” Molle said. But there are also private schools and out-of-state schools that some students have on their interest list. The majority have made the tests optional, leaving applicants hoping for a high score to help their admissions chances. Those schools are a big reason Hewitt’s peers continue to take the tests, he said. Occidental College and USC, both located in Los Angeles, are going test-optional this year. “Applicants will not be penalized or put at a disadvantage if they choose not to submit SAT or ACT scores,” USC’s website reads. “USC’s student selection process has always been holistic, and we are confident in our ability to identify student potential using the totality of what’s presented to us.” All eight Ivy League schools and Stanford are also letting applicants choose whether to submit test scores. California Baptist University in Riverside is using the pandemic setbacks as an opportunity to experiment with going “test blind” until fall 2023. “We will collect data to study the impacts, if any, of being ‘test blind’ and then make a longer-term solution after that,” Dean of Admissions Taylor Neece said in an email. More pandemic changes Test-optional hesitancy isn’t all that’s new for this year’s high school seniors hoping to nail down their higher education plans. College visits, that rite of passage for so many, have moved into the virtual sphere. Most universities only just started opening their campuses for students enrolled this fall. “While it may be too soon to state which practices will stay indefinitely, the pandemic helped catalyze innovations in providing virtual support,” said Molle, who works in the Cal State Chancellor’s Office. “In some cases, new practices may be combined with traditional practices to offer more options for incoming students and families to learn about CSU campuses.” The online menu of tours, information sessions, orientation meetings and counselor conferences are here to stay – at least for this year, officials from multiple universities said. “I like that when the time came, colleges knew they needed to change and gave students virtual options. Almost all of them are free, and traveling can be expensive,” Hewitt said. With the help of online programming, seniors can make more informed decisions when choosing where to commit, Hewitt said. Of course, interactive online experiences aren’t the same as physically being on campus, said Hewitt, who has visited several colleges in person. But it’s a step up from just looking at posted photos. Leveling the playing field With no standardized test scores to show and new ways for students to get engaged online, the college admissions process is rapidly changing. “People who come from a family of higher income really had more opportunities to be prepared,” Medina said. “They had more resources to help them with the application process, to help them with the SAT process. But now, that’s off the table.” And though admissions requirements are different, some things will stay the same. Fred Lentz, co-founder of the La Habra-based college admissions nonprofit Advance!, said “the kids that are going to do well beforehand, they’re going to do well afterward.” Lentz, a retired high school teacher who worked with many underrepresented students, said test-taking is a skill that many students don’t have the resources to learn. He said he’s glad that other aspects of an application, such as the personal statement, recommendation letters and extracurricular activities, will carry more weight now that the SAT and ACT are optional. “We had a student, she spent four years sleeping on the floor in the bedroom, studying by flashlight. She got a 4.6, now she’s going to Berkeley,” Lentz said. “Tell me that the SAT and the ACT is a better definition for her chances for success than what I told you.” Source: The Press Enterprise.

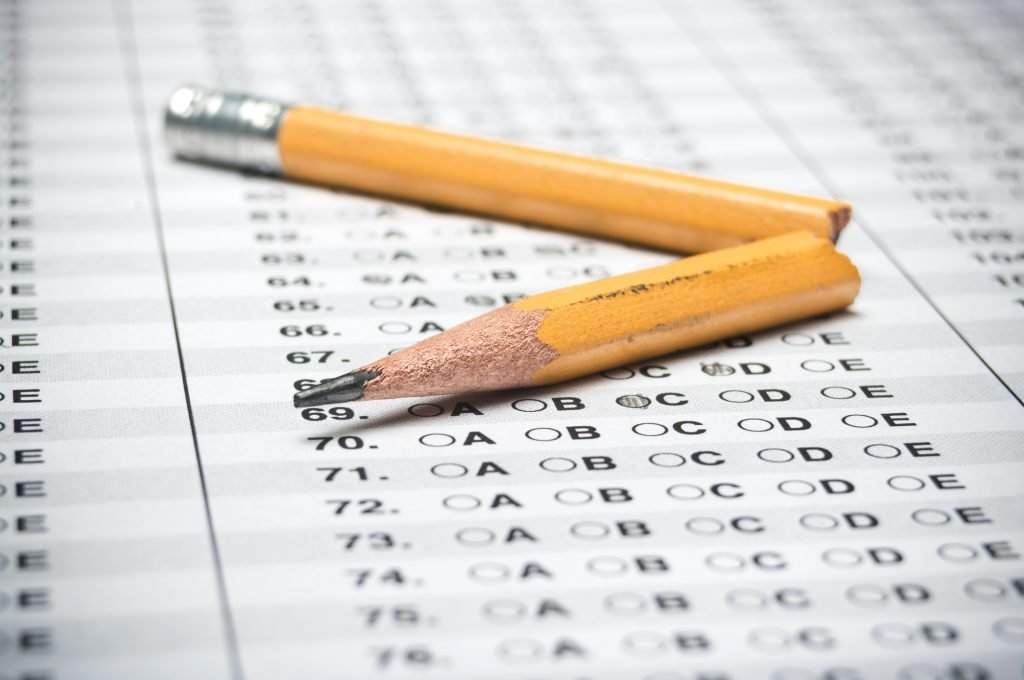

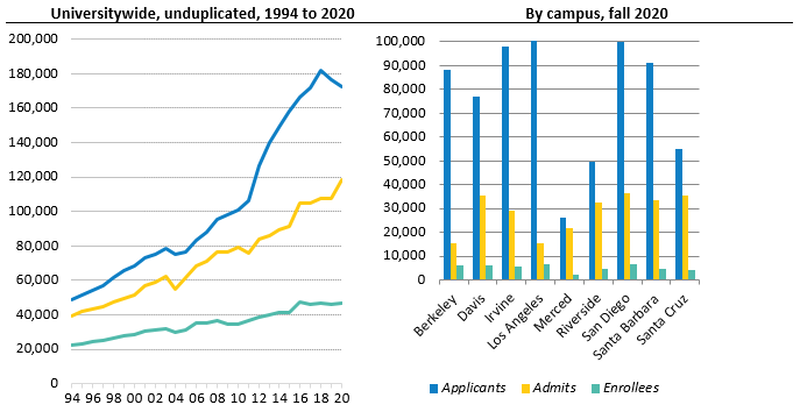

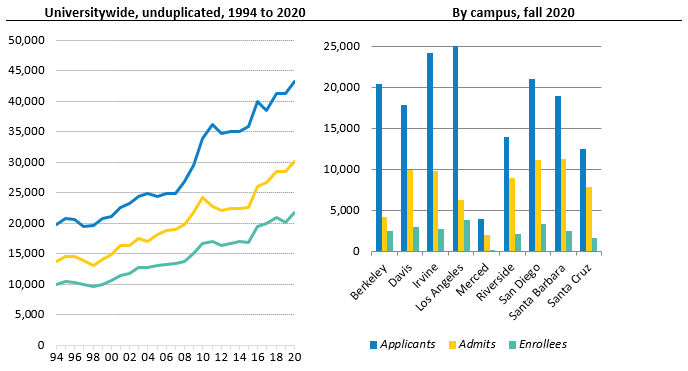

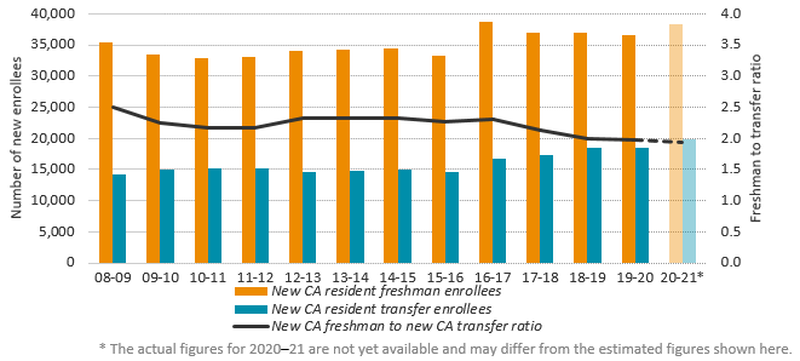

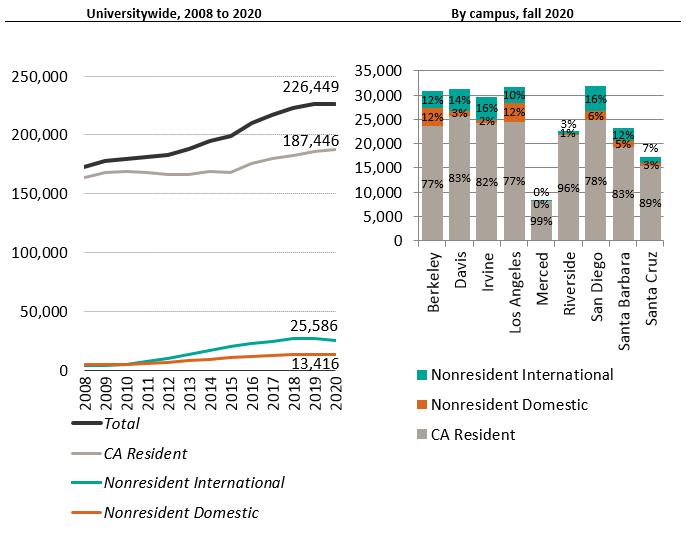

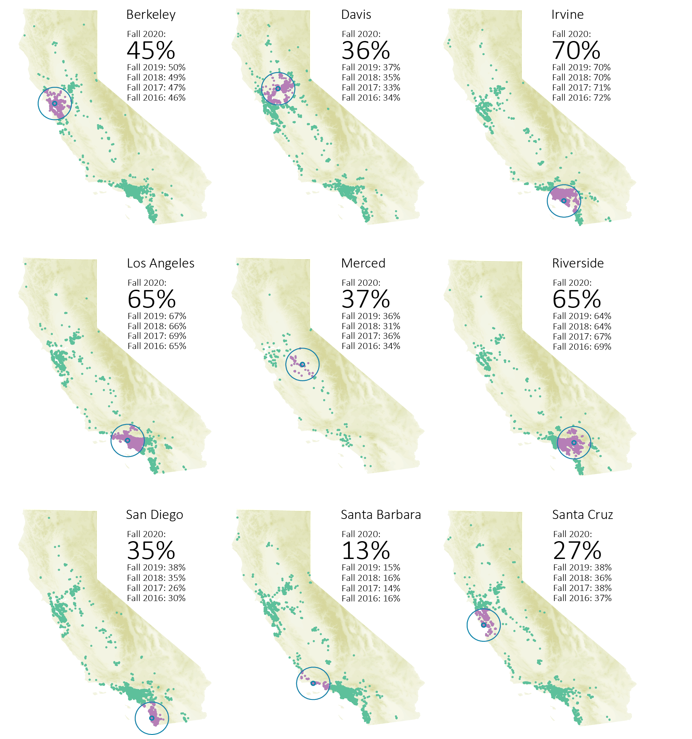

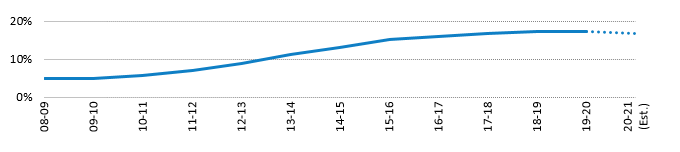

GOALS One of the University of California’s highest priorities is to ensure that a UC education remains accessible to all Californians who meet its admissions standards. This goal is articulated in California’s Master Plan for Higher Education, which calls for UC to admit all eligible freshmen and transfers, with freshman eligibility designed to capture the top 12.5 percent of California public high school graduates. It also calls for UC to admit all eligible transfer students from California Community Colleges (CCCs) who apply. Of the over 215,000 applications for admission in fall 2020, about 172,000 students applied as freshmen and 43,000 as transfers. Campus admission decisions are based on a comprehensive review of qualifications and establish the incoming California resident class size based on State funding. Over the last five years, UC’s total undergraduate enrollment of California residents increased by more than 18,000: 1,500 in fall 2020, 2,500 in fall 2019, 3,000 in fall 2018, 4,000 in fall 2017, and 7,000 in fall 2016. For 2020–21, UC is also estimated to have achieved its enrollment capacity goal of enrolling a 2:1 systemwide ratio of freshman to transfer California resident undergraduates, excluding Merced, for the fourth year in a row. The UC Transfer Pathways program supports this goal by helping community college students prepare for transfer admission to the most popular majors at UC campuses. Under a new agreement with the California Community Colleges, UC has created a Transfer Guarantee program, Pathways+, for community college students who meet certain criteria. This campus and major guarantee accompanies and is complimentary to UC's systemwide transfer guarantee program. The first cohort for the Pathways+ program is expected to enroll in fall 2021. ADMISSIONS — FRESHMEN UC utilizes a comprehensive review process to make admission decisions, considering not only completion of rigorous college preparatory courses and high school GPA, but also talents, special projects, accomplishments in light of life experiences and circumstances, extracurricular activities, and community service. The rapid growth in freshman applications to UC over the past two decades demonstrates the increased demand for a college education, the growth of California’s population, and UC’s continued popularity. UC continues to reach its Master Plan goals by guaranteeing admission to California resident applicants who are either in the top nine percent of high school graduates statewide or the top nine percent of graduates from their own high schools. Qualified freshman applicants are offered an opportunity to be admitted to another UC campus if they do not receive an offer of admission from the UC campuses where they applied. ADMISSIONS — TRANSFERS Almost all transfer students enter UC as upper-division juniors. Campus enrollment targets are based on State funding as well as capacity in major programs at the upper-division level. UC’s Transfer Pathways identify a common set of lower-division courses for each of 20 of the most popular majors among transfer applicants. The Transfer Pathways present a clear roadmap for prospective transfers to prepare for their majors and be well positioned to graduate in a timely fashion from any UC campus. In fall 2020, the third year of the Transfer Pathways, those indicating Pathway-based preparation represented 50 percent of all CCC admits and 51 percent of all CCC enrollees. Many of these students also participated in other preparatory programs such as Transfer Admissions Guaranteed (TAG) and Intersegmental General Education Transfer Curriculum (IGETC). Transfer Pathways Majors Anthropology Computer Science Molecular Biology Biochemistry Economics Philosophy Biology Electrical Engineering Physics Business Administration English Political Science Cell Biology History Psychology Chemistry Mathematics Sociology Communication Mechanical Engineering In April 2018, UC signed an agreement with the California Community Colleges (CCCs) to guarantee a place within the UC system to students who complete one of the Transfer Pathways and achieve the requisite grade point average (GPA). The new Pathways+ program launched in August 2019. ENROLLMENTS The University enrolled over 226,000 undergraduates in fall 2020. The University enrolls freshman and transfer students from almost every county of California. UC’s Eligibility in the Local Context (ELC) policy is designed to increase the overall geographic diversity of freshman entrants. Undergraduate Enrollment, Fall 2020 New Freshmen 46,716 New Transfers/Other[1] 21,960 Continuing Students 157,773 TOTAL 226,449 As academic qualifications have improved over the last decade, UC has maintained access for populations historically underserved by higher education. In fall 2020, 34 percent of new undergraduates received Pell Grants, a marker for low-income status. About 41 percent of UC’s entering students are first-generation, meaning neither parent graduated from a four-year college. These students are more likely to be from an underrepresented group (URG, African American, Hispanic/Latinx and Native American/Alaska Native students), to have a first language other than English, to enter as a transfer student, to be female, and/or to have a lower income than students with at least one parent who graduated from a four-year college (1.2.1). The share of all undergraduates who are nonresident domestic and international students has increased in recent years, though their proportion is still much lower than at comparable public research universities. In 2019–20, the share of new undergraduates paying nonresident tuition went down slightly while the share of all undergraduates paying nonresident tuition went up slightly (1.4.4). In May 2017, UC adopted a policy[2] affirming that nonresident undergraduates “will continue to be enrolled in addition to, rather than in place of, funded California undergraduates at each campus.” The policy also capped nonresident enrollment at 18 percent for five UC campuses (Davis, Merced, Riverside, Santa Barbara, and Santa Cruz) and, for the remaining four campuses (Berkeley, Irvine, Los Angeles, and San Diego), at the proportion each campus enrolled in 2017–18. The policy went into effect for the 2018–19 academic year. Having California students learn and live alongside students from backgrounds and cultures different from their own is part of a world-class educational experience. California students also benefit from the extra tuition paid by nonresident undergraduates, which is about $30,000 more per year than the amount paid by residents. That tuition helps to fund faculty hires, instructional technology, student advising, and other services that directly benefit California students. [1] Other types of new students include those enrolling for a second baccalaureate or with limited status (not seeking a bachelor’s degree). [2]Regents Policy 2109: Policy on Nonresident Student Enrollment: regents.universityofcalifornia.edu/governance/policies/2109.html. ADMISSIONS AND ENROLLMENT TRENDS Freshman applicants have gone up from 68,000 to 172,000 over the past two decades, averaging four percent growth per year. In fall 2020, the number of applicants decreased two percent compared to the previous year, while the number of students admitted went up ten percent and the number of enrollees went up two percent (1.1.1). While the fall 2020 incoming cohort applied to UC before the COVID-19 pandemic, they made choices about whether and where to attend college during the start of the pandemic, and entered UC during a time of distance learning. Application numbers are about the same as the year before but admitted students were deciding to come to UC at a lower rate, leading campuses to admit a higher proportion of applicants in order to meet enrollment goals. Fall transfer applicants nearly doubled over the last 20 years, with average annual growth of four percent. In fall 2020, transfer applicants and admits both increased by five percent compared to the previous year, while enrollees went up eight percent (1.1.2). The Master Plan specifies that the University maintain a 60:40 ratio of upper-division to lower-division students, which corresponds to a 2:1 ratio of new California resident freshmen to new California resident transfers. UC has moved from 2.3:1 in 2016–17, to an estimated 1.9:1 in 2020–21 (Universitywide). The Universitywide ratio excluding Merced is also estimated to be 1.9:1 for 2020–21, achieving the systemwide goal for this metric for a fourth year. The University continues to work toward achieving this ratio for each campus (except Merced) (1.1.3). Overall undergraduate enrollment (new and continuing students) continued to grow in fall 2020. Total enrollment was over 226,000 in fall 2020, up less than half a percent from the year before. This includes an increase in California residents of over 1,500, following increases of over 7,000 in fall 2016, over 4,000 in fall 2017, over 3,000 in fall 2018, and over 2,500 in fall 2019 (1.1.4).ACADEMIC PREPARATION Freshmen entering UC are increasingly well prepared, as shown by changes in the number of college preparatory courses and high school GPA over time (1.3.1). Transfer students are also increasingly well prepared, as measured by college GPA over time (1.3.2). GEOGRAPHIC ORIGINS AND NONRESIDENTS UC has a lower proportion of out-of-state undergraduates than other public AAU universities. In fall 2020, only 17.2 percent of UC’s enrollees were out-of-state or international, compared with 30.5 percent for other AAU public institutions (1.4.1). About 36 percent of freshmen and 49 percent of transfer students entering UC campuses come from within 50 miles of campus. These numbers are relatively stable and have risen only slightly over the past few years (1.4.2, 1.4.3). The percentage of all undergraduates paying nonresident tuition and the percentage of new undergraduate students paying nonresident tuition went up slightly in 2019–2020 (1.4.4). LOOKING AHEAD The University of California Board of Regents at its May 2020 meeting unanimously approved the suspension of the standardized test requirement for all California freshman applicants until fall 2024, providing time for the University to create a new test that better aligns with A–G curricular standards. However, if a new test does not meet specified criteria in time for fall 2025 admission, UC will eliminate the standardized testing requirement for California students. Enrollment of new freshman and transfer students has been fairly steady for the last few years, but will need to grow for UC to meet its goal of awarding an additional 200,000 degrees (for a total of 1.2 million) by 2030. State funding is crucial for reaching this goal. UC also continues to work to close equity gaps. In 2020, 61 percent of California public high school graduates were from underrepresented groups (URGs) while 38 percent of new freshman enrollees at UC were from these groups, for a 23-percentage point gap. Although unduplicated freshman applicants went down by two percent in 2020 compared to 2019, they remained above the levels for all years prior to 2018. From 2011 to 2018, applicants increased 71 percent (or about eight percent per year), from about 106,000 to about 182,000, compared to a 42 percent increase in the seven-year period between 2004 and 2011 (or about five percent per year), from about 75,000 to 106,000. The 71 percent growth represents about 76,000 applicants, including about 35,000 California residents. Most campuses admit less than half of freshman applicants. Many applicants apply to more than one UC campus; in fall 2020, UC applicants applied to an average of 3.9 campuses. Freshman applications increased at Berkeley, Irvine, Merced, and San Diego, and decreased for all other campuses in fall 2020. For data tables on UC freshman applicants, admits, and enrollees by campus over time, see: universityofcalifornia.edu/infocenter/admissions-residency-and-ethnicity. Transfer applicants, admits, and enrollees are higher than ever. 1.1.2 Transfer applicants, admits, and enrollees, Universitywide and UC campuses, Fall 1994 to 2020 Transfer applications and admits increased by five percent, and enrollees increased by eight percent in fall 2020. Over 43,000 transfer students applied, over 30,000 were admitted, and almost 22,000 enrolled in fall 2020. Consistent with UC’s commitment to transfer students from California Community Colleges (CCCs), fall enrollment of new CCC California resident transfers has more than doubled since 1994, from 8,400 to 18,100. The average transfer applicant applies to 3.7 UC campuses, compared to 3.9 for the average freshman applicant. For data tables on UC transfer applicants, admits, and enrollees by campus see: universityofcalifornia.edu/infocenter/admissions-residency-and-ethnicity. UC has met the systemwide goal of a 2:1 ratio of California resident freshmen to transfer students and is on track to meet the goal at all campuses. 1.1.3 New California resident freshmen and transfer students, Universitywide, 2008–09 to 2020–21 The California Master Plan calls for UC to accommodate all qualified resident California Community College (CCC) transfer students. It specifies that the University maintain at least a 60:40 ratio of upper-division (junior and senior) to lower-division (freshman and sophomore) students to ensure adequate upper-division spaces for CCC transfers. To do so, UC aims to enroll one new California resident transfer student for every two new California resident freshmen, or 67 percent new resident freshmen to 33 percent new resident transfer students.2 UC has moved from 2.3:1 in 2016–17 to an estimated 1.9 in 2020–21 (Universitywide). Excluding Merced, the ratio for 2020–21 is also estimated to be 1.9:1, meeting the systemwide goal four years in a row.3 San Diego met it in 2019–20 and Riverside was estimated to meet it in 2020–21. Santa Cruz met the goal in 2018–19 and 2019–20, but in 2020–21 did not meet the goal primarily due to an unusually large freshman class.

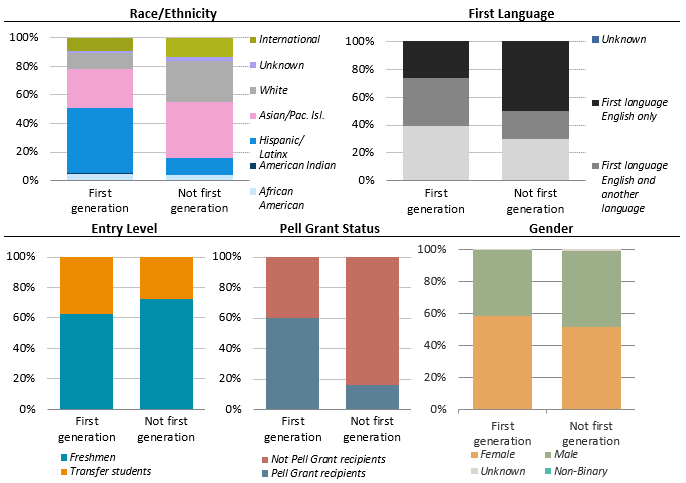

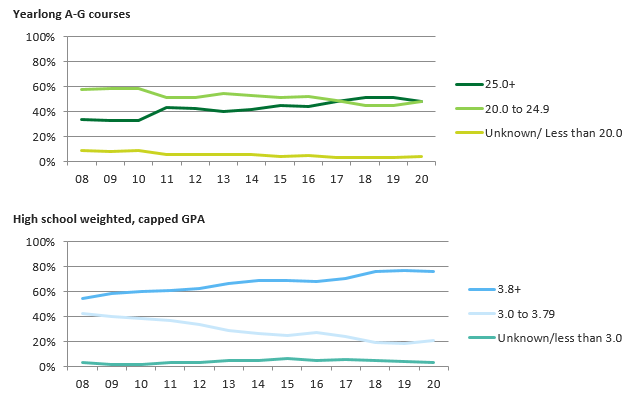

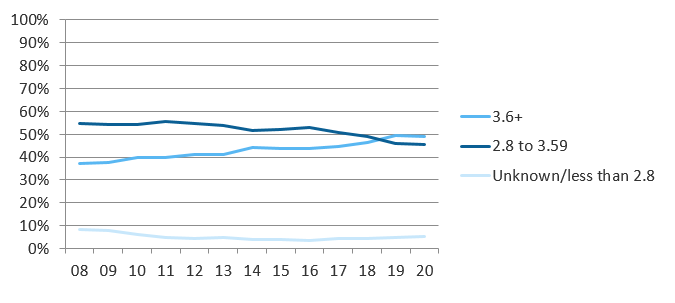

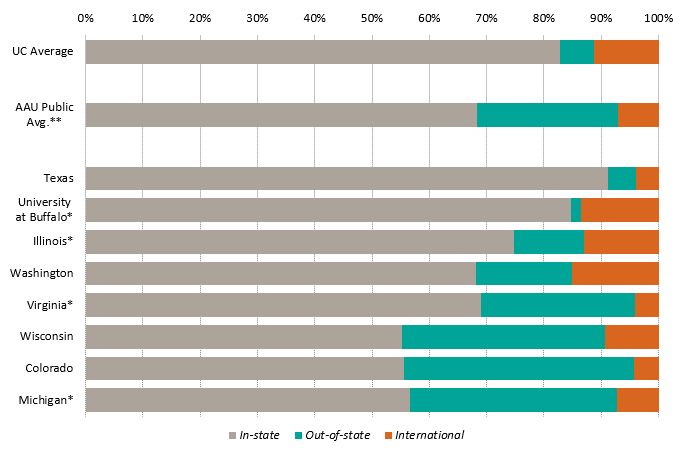

UC’s fall undergraduate headcount grew slightly between fall 2019 and fall 2020, including over 1,500 additional California residents. 1.1.4 Undergraduate headcount enrollment, Universitywide and UC campuses, Fall 2008 to 2020 The University and the state share the goal of expanding access to a UC education. The University enrolled over 1,500 additional California residents in fall 2020 compared to fall 2019, following increases of 2,500, 3,000, 4,000 and 7,000 in the four prior years, for a total of over 18,500 over five years. 1.2 DEMOGRAPHIC OUTCOMES UC’s entering first-generation students are more likely to be from an underrepresented group (URG), to enter as transfer students, and/or to be Pell Grant recipients. 1.2.1 Entering students by first generation status, race/ethnicity, first language spoken at home, entry level, Pell Grant status, and gender, Universitywide, Fall 2020 A little over half (50 percent) of entering first-generation students in fall 2020 are from URGs, compared to 16 percent of not-first-generation students. Almost two-fifths (39 percent) of first-generation students’ first language was not English, versus 30 percent for others. Over one-third (37 percent) of first-generation students entered as transfers, versus 27 percent for others. Three-fifths (60 percent) of first-generation students are lower-income Pell Grant recipients, versus 16 percent for others. And nearly three-fifths (58 percent) of first-generation students are female, compared to just over half (52 percent) of others. 1.3 PREPARATION OUTCOMES Freshmen entering UC are increasingly well-prepared. 1.3.1 A–G (college preparatory)1 courses and weighted, capped high school grade point average (GPA)2 of entering freshmen, as share of class, Universitywide, Fall 2008 to Fall 2020 The academic indicators of UC’s entering freshmen have improved over time, as reflected by an increase in the share of students completing 25 or more college-preparatory courses and having a 3.8 or higher high school GPA. Despite slight downturns in 2020, from 2008 to 2020, the first indicator went up from 33 percent to 48 percent, while the second went up from 54 percent to 76 percent. 1.3 PREPARATION OUTCOMES UC transfer students in fall 2020 were better prepared academically than their counterparts a decade ago, as measured by their grades. 1.3.2 College grade point average (GPA)1 of entering transfer students, as share of class, Fall 2008 to Fall 2020, Universitywide The academic qualifications of transfer students entering UC have improved over time, as reflected by an increase in the share of students having a 3.6 or higher college GPA, from 37 percent in fall 2008 to 49 percent in fall 2020. 1.4 GEOGRAPHIC ORIGINS AND NONRESIDENTS UC has a substantially lower proportion of out-of-state undergraduates than other AAU universities. In fall 2020, only 17.2 percent of UC’s enrollees were out-of-state or international, compared with 30.5 percent for other AAU Public institutions. 1.4.1 Residency of undergraduate students, Universitywide and comparison institutions, Fall 2020 UC’s priority is to enroll California residents. Campuses enroll nonresident students based on available physical and instructional capacity and the campus’ ability to attract qualified nonresident students. Nonresidents provide geographic and cultural diversity to the student body. They also pay the full cost of their education. In 2019–2020, systemwide tuition and fees for a nonresident undergraduate were $42,324, compared to $12,570 for California resident students. Nonresident applicants must meet higher criteria to be considered for admission. The minimum high school GPA for nonresident freshmen is 3.4, compared to 3.0 for California freshmen. The minimum college GPA for nonresident transfer students is 2.8, compared to 2.4 for California residents. 1.4 GEOGRAPHIC ORIGINS AND NONRESIDENTS UC campuses attract freshmen from nearby regions and the major urban areas of California, with a systemwide local attendance rate of 36 percent. 1.4.2 Percentage of new CA resident freshman enrollees whose home is within a 50-mile radius of their campus, UC campuses[1], Fall 202 1.4 GEOGRAPHIC ORIGINS AND NONRESIDENTS Local enrollment rates for transfers are higher than for freshmen, with 49 percent enrolling at a UC campus within 50 miles of their homes. 1.4.3 Percentage of new CA resident transfer enrollees whose home is within a 50-mile radius of their campus, UC campuses[1], Fall 2020 1.4 GEOGRAPHIC ORIGINS AND NONRESIDENTS The proportion of undergraduate students paying nonresident tuition declined slightly in 2020–2021. 1.4.4 Percentage of undergraduate enrollees paying nonresident tuition by academic year1, Universitywide, 2008–2009 to 2020–2021 .Systemwide, the share of all undergraduates paying nonresident tuition rose from five percent to 17.6 percent between 2009–2010 and 2019–2200. From 2009–2010 to 2015–2016, the proportion of undergraduates paying nonresident tuition went up from five percent to 15.3 percent, this increase in this period coincides with a period of reductions in State funding for UC due to the Great Recession. Starting in 2016–2017 as enrollment of new California residents increased, the proportion of undergraduates paying nonresident tuition leveled off to 17.5 percent between 2017–2018 to 2019–2020 During the COVID-19 pandemic, the estimated percentage dropped to 16.8 in 2020-2021. The proportion of nonresident students at individual campuses varies depending on a campus’ capacity, and its ability to attract nonresident students, as well as its nonresident cap under a policy approved in May 2017, which applies to total undergraduate numbers. Under the policy, effective in 2018–2019, nonresident enrollment is limited to 18 percent at five UC campuses. At the other four campuses where the proportion of nonresidents already exceeded 18 percent — UC Berkeley, UC Irvine, UCLA, and UC San Diego — nonresident enrollment is capped at the proportion that each campus enrolled in 2017–2018 Source: Accountability Report 2021 from University of California. Following an unprecedented year marked by the coronavirus pandemic, hybrid instruction and travel restrictions, the University of California announced today (July 19) that its campuses made record-breaking admission offers to a new class of undergraduates for fall 2021.

Systemwide freshman admissions jumped 11 percent over 2020, rising to 132,353 from 119,054. Admission of California freshmen reached an all-time high this year with 84,223 students, an increase of 5.34 percent over the 79,953 from 2020. Students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups comprise 43 percent of admitted California freshmen, the highest proportion of an incoming undergraduate class and the greatest number in UC history at 36,462. The University also admitted the largest-ever class of California Community College transfer students, notching up to 28,453 from 28,074, a year-over-year increase of 1.35 percent. The vast majority of these transfer students are California residents (25,700). Notably, 53 percent will be the first in their family to earn a four-year college degree. “These remarkable numbers are a testament to the hard work and resiliency of students and their families across California,” said President Michael V. Drake, M.D. “I am particularly heartened by the social and economic diversity of those offered a place at UC. Fall will be an exciting time on our campuses.” Other highlights include Latinx students comprising the largest ethnic group (37 percent) of admitted California freshmen for a second time, up nearly 9 percent to 31,220 from 28,662, following the previous record in 2020. Systemwide, admissions of African-American students grew by 15.6 percent, rising to 4,608 from 3,987 in 2020. Meanwhile, admission of California freshmen who would be first-generation college students held steady at 45 percent. There are also remarkable achievements across campuses. The locations with the greatest annual overall year-over-year freshman admission gains include UC Davis up 19.2 percent (42,726 from 35,838), UC Irvine up 6.9 percent (31,261 from 29,245) and UC San Diego up 6 percent (40,616 from 38,305). UC Merced had the highest percentage of first-generation resident freshman admissions (59 percent) with a total of 13,136. UC San Diego had the highest number of community college transfers (11,358), an increase of nearly 4 percent. “As the data make clear, UC is continuing to honor its commitment to guarantee admission to high-performing California high school students and providing a clear pathway for talented community college students to join us,” said Han Mi Yoon-Wu, executive director of Undergraduate Admissions at UC. “We are proud to be able to welcome so many exceptional young people to UC.” Several factors may explain the rise in admissions. Fall 2021 applications from California freshmen were up more than 13 percent, rising to 128,266 from 113,471 in 2020. Campuses made efforts to admit as many qualified California students as space could allow given the expanded pool of highly qualified, hardworking students this year. The end of UC’s standardized testing requirement may have also encouraged more students to apply. Additionally, in recognition of the many challenges COVID-19 posed for prospective students and their families, the University made temporary adjustments to admission requirements, including suspending the letter-grade requirement for high school classes taken in winter, spring or summer terms of 2020 and the full 2020–21 academic year. UC also provided flexibility for students who needed more time to meet registration, deposit and transcript deadlines last year. UC hoped these changes would further support students who faced barriers during a challenging year marked by cancelled classes and schools that switched to pass/fail grading. The preliminary admission figures released today include applicants admitted from waitlists and freshman and transfer referral pools. The data are subject to change as campuses verify that conditions of admission are met. Data tables with campus-specific information for both freshmen and transfer students are available here. Source: University of California The University of California’s Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSI) Initiative recently released a report titled “La Lucha Sigue: The University of California’s Role as a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution System.” With an eye on the Latinx communities’ future in-state growth and vital contributions to California’s economy, the HSI Initiative gives UC leaders a window into the Latinx student experience, while highlighting California’s looming economic challenges.

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, the state faces a shortage of 1.1 million college graduates by 2030. In order to address this shortfall, the report details how Latinx communities will make up an even larger share of UC campus populations and offers a blueprint for UC leaders on how to foster Latinx student success in the years ahead. As “La Lucha Sigue: The University of California’s Role as a Hispanic-Serving Research Institution System” states, this document “provides recent, foundational information grounded in data to provide readers an understanding of the changing California demographics that have led to UC’s high Latinx enrollment numbers. In an effort to move conversations beyond access and enrollment, this report also showcases academic outcomes for Latinxs enrolled at UC over time.” It goes on to state, “Ultimately, as the authors of this report, we perceive an ongoing need to focus on Latinx students and their experiences at UC. We contend that by leveraging UC’s role as an [Hispanic-Serving Research Institution] HSRI system, the university is well-positioned to make significant contributions to research, policy, and practice across the nation.” UC has seen exponential growth in its Latinx student populations. In 1992, UC’s Latino Eligibility Taskforce found that just 4 percent of California Latinx high school graduates were eligible for admission to UC. Now, 45 percent of Latinx public high school graduates are UC-eligible. This growth has propelled five out of nine undergraduate UC campuses to secure federal designations as Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs): UC Irvine, UC Merced, UC Riverside, UC Santa Barbara and UC Santa Cruz. The remaining four undergraduate campuses, UC Berkeley, UC Davis, UCLA and UC San Diego, are emerging HSIs, deemed as institutions with 15 to 24 percent Latinx undergraduate enrollment, as defined by Excelencia in Education, a national nonprofit dedicated to Latinx student success in higher education. As an HSRI system, UC is now poised to build on the tremendous progress already made. “UC-HSI provides us with a progress report for UC to better understand how our efforts have borne fruit, and a blueprint for transformational leadership for us to become the model Hispanic-Serving Research Institution system in support of Latinx and other students from underrepresented groups,” said Dr. Yvette Gullatt, vice president for Graduate and Undergraduate Affairs and vice provost for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. As the report demonstrates, enrollment numbers for Latinx students at UC are surging. From 2009-19, UC saw an 89.8 percent increase in enrolled Latinx students with the greatest increases in Latinx enrollment occurring at UC’s now-designated Hispanic-Serving Institutions: Irvine, Merced, Riverside, Santa Barbara and Santa Cruz. Collectively, these five campuses increased their Latinx student enrollment by over 90 percent during the same period. The report also finds areas for additional growth and strategic improvement at UC including in Latinx student graduation rates, in fostering greater Latinx student postgraduate enrollment, and in recruiting additional Latinx faculty. In its study, the UC-HSI Initiative identifies key findings for UC to consider. Some of them include leveraging the University’s HSI status to expand efforts beyond the recruitment and enrollment of Latinx students to the retention, timely graduation, and post-baccalaureate pathways for these students. As the authors highlight, “by increasing the number of Latinx graduate students and retaining and graduating them, UC can foster the next generation of faculty, leaders, and critical thinkers who are representative of the demographics of the state.” The authors also suggest that by creating a definition of “serving” for individual campuses and the UC system as a whole, a conversation can begin on creating new indicators for academic success that better encompass the holistic experiences of Latinx students at UC. Additionally, the report urges the University to consider opportunities for creating a statewide learning community between UC, the California State University (CSU) system, and California Community Colleges (CCC) to share knowledge, expertise, and best practices for Latinx student success as this population becomes an even greater share of California’s college student population. The University of California Hispanic-Serving Institutions Initiative plans to release additional reports in this series exploring UC’s unique position as a doctoral-granting, research-intensive, public HSRI and further detailing how Latinx UC students experience campus climate. You may find further information on the Hispanic-Serving Institutions Initiative here. Source: University of California Website Taking the following courses will prepare you to major in mechanical engineering at any UC campus. Course expectations

Use ASSIST to find the specific classes offered at your community college that will satisfy the expected coursework at a particular UC campus. In addition to the coursework above, you will need to fulfill minimum requirements expected of all transfer applicants to UC. In particular, students are required to complete two English reading and composition courses no later than the spring term prior to transfer. If you’re interested in transferring to the Berkeley campus, be sure that these two transferable English reading and composition courses articulate to Berkeley’s required courses. If you're working on an Associate Degree in mechanical engineering at your community college, there's a lot of overlap with UC Transfer Pathway coursework. When you have options, try to select courses for your Associate Degree that meet both your community college and UC requirements. The difference between what UC expects and what some community colleges require is linear algebra, a full sequence of chemistry with lab and circuits with lab; however, UC does not expect materials science and engineering. Applicable majors The Mechanical Engineering Pathway applies to the degree programs listed below. More degree programs may be added in the future so you should check back periodically to see if your major has joined this list.

Admission to different UC campuses and majors varies in competitiveness depending on how many students apply and how many slots are available. As a result, the minimum GPA and grade requirements for particular courses may vary from campus to campus. Make sure to look on the campus admissions websites to find minimum expected grade point averages for the major you are interested in. Source: University of California Website. Getting to UC takes time. So we’ve created a range of tools to help you plan. These tools will keep you on track, and let you check your progress whenever you need to. ASSIST helps you find the courses you need to meet your transfer requirements. UC TAP tracks your progress toward meeting those requirements. Transfer Pathways Guide tells you which courses work with a specific Transfer Pathway. ASSIST

The ASSIST tool lets you know which of your community college classes will count toward your UC degree. That helps you take the right courses from the get-go, and transfer as smoothly as possible. ASSIST UC TAP The Transfer Admissions Planner (UC TAP) helps you plan your coursework and map your progress. So you always know how close you are to meeting UC’s minimum requirements, and what’s left to do. You can use UC TAP for any community college transfer process, including a Transfer Admission Guarantee (TAG) with one of our six participating campuses. UC TAP Transfer Pathways Guide The Transfer Pathways Guide lets you check if your community college courses fulfill the specific requirements of your chosen Transfer Pathway. It’s more focused than ASSIST, in that it's targeting the particular courses that make up each of the 20 Transfer Pathways. (So if you want to keep your options more open, ASSIST is better for you.) Transfer Pathways Guide Source: University of California Website There are a few different ways to get into the UC. To make it easier, we’ve created three guided options. One of these will help you move through the process in the best way for you. You don’t have to choose one of these options but many people do, as it’s much simpler. Let’s find the right option for you. If you know your major – follow Transfer Pathways. If you have a dream campus – use TAG. If you’ve decided on both – try Pathways+ Transfer Pathways

You have a major in mind.Decided on a major but want to keep your campus options open? The UC Transfer Pathway program may be right for you. This means you take a single set of courses to get ready for your major—and you can choose from any of our nine undergraduate campuses. You’ll get clear guidance on what classes you need to take, which hugely increases your chances of studying at a UC campus. Plus, you’ll be in a great position to succeed once you get here. Keep in mind that Pathways is designed for our most sought-after majors. That might not include yours—so please check! Find everything you need to know about Transfer Pathways » TAG You know where you want to study.If you have your eye on a particular campus, then good news: six UC campuses offer our Transfer Admission Guarantee (TAG) program. When we say guarantee, we mean guarantee. You submit a separate TAG application to your chosen campus, and if you meet the course and GPA requirements, then you’re in. You have a 100% guaranteed place in your major at your chosen campus. Learn more about TAG » Pathways+ You picked your major, and it’s included in the Transfer Pathways program. You found your campus, and it offers a TAG.Pathways+ is a great option if your major is covered by Pathways, and you want the freedom to explore multiple campuses while ensuring a spot at one of our six TAG campuses. It gives you the best of both worlds: a guaranteed spot at UC, and the support you need to hit the ground running when you get here. Get started with Pathways+» Source: University of California Website So, you want to transfer to UC. Great! We know the process can be a little intimidating, so we’ve broken it down. These are the three things you need to do: Plan what you want to study, and where Prepare ahead of time with your goals in mind Track your progress until it’s time to transfer Plan

When you’re planning to transfer, keep three things in mind:

Use the Transfer Admission Planner (UC TAP) If you're enrolled at a California community college, our UC Transfer Admission Planner (UC TAP) helps you track your progress towards our admission requirements. It can also serve as your application for the UC Transfer Admission Guarantee (TAG). Use the Transfer Admission Planner to enter your coursework (or plan upcoming terms). Talk to a transfer advisor Your community college will have a Counseling Center, including a transfer center with transfer advisors. You should definitely seek out their advice. You may even be able to meet with a UC admissions representative in the transfer center to discuss your transfer options. Join us at a transfer event We host them year-round, all across the state. They’re a great place to ask questions and meet people on the same path as you. Prepare Once you’ve worked out your plan, it’s time to put it into action. Here are the four things you’ll need to work toward as you go through your transfer process. 1. The basics: math and English There’s a good chance you’ve already done math and English assessments to enroll in your college. Just make sure that whatever courses you're doing, you’re working toward passing math and English classes that are UC-transferable. Use our ASSIST tool to help you choose eligible courses. We recommend you start taking these courses early. They'll help you build the skills you need for university classes. And some UC campuses need you to complete English and math by the end of the fall term the year before enrolling. Starting early also gives you time to pass all the classes you need to in order to transfer. For example: Your college has placed you in Intermediate Algebra. But your UC campus needs you to pass Pre-calculus. You’ll want to take Intermediate Algebra as soon as possible, so you’ll also have time to complete Pre-calculus before you transfer. 2. Preparing for your major Once you’ve got a sense of what you want to major in, make sure it’s right for you. Get to know the coursework for that major at your preferred UC campuses. Wherever you plan to apply, check your major in their course catalogs. Do the classes seem interesting? Are you excited about the introductory courses, as well as the advanced courses? It’s important to think carefully about these things now. There’s no point going to all this effort, only to end up doing something you don’t enjoy. Laying the groundwork When it comes to getting into your major, there are two more things to consider: required courses, and recommended courses. Your major probably has specific requirements before you can transfer. So make sure you’re enrolled in those classes. Plus, there’s a range of recommended courses. And we would—you guessed it—recommend taking some of these. Completing them before you transfer boosts your chances of getting into the major you want, and graduating on time. Courses for any campus Decided on a major, but want to keep your campus options open? Try following a UC Transfer Pathway. The Pathways cover our most sought-after majors, and give you a single set of courses that let you transfer to any UC campus. About Transfer Pathways » 3. Picking general education classes It’s great to be dedicated to one subject, but a broad base of knowledge is important too. That’s why we have general education requirements, which can vary across UC. Depending on your major and campus, you may want to start taking these classes at your community college. About general education requirements » 4. UC's minimum admission requirements Whatever your chosen major and campus, you’ll need to meet UC’s minimum requirements for transfer admissions. Your major preparation and general education courses will count toward these. But there may still be a few gaps to fill in, so check regularly to make sure you’re on track for transfer. You (and your advisors) can use the UC TAP tool to plan and track your progress. For example: If you're a STEM major, you'll be taking lots of science and math courses. But don't forget—you also need to take humanities and/or social sciences courses to fulfill UC minimum requirements. Track We know the transfer process can be complicated. That’s why we have guided transfer paths to help you get to UC in a way that works for you. Whether your heart’s set on a specific campus, or you’re passionate about a certain major, we’ll get you on the right path. Once you’ve chosen that path, we have a range of tools to help you stay on track:

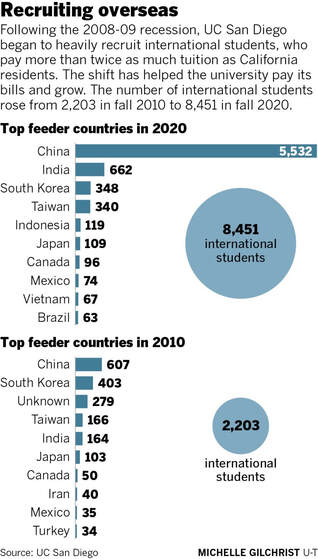

The possibility of another big wave of growth is causing its own set of problems As an elite school that educates the masses and pumps money into the economy, UC San Diego is rarely the target of strong criticism. But a lawmaker unloaded last week, accusing UCSD and its sister campuses at Berkeley and Los Angeles of betraying Californians. Assemblyman Phil Ting (D-San Francisco) told the Union-Tribune that the UC system — and those three campus in particular — “focused on admitting out-of-state students at the expense of in-state students. They deny that. But if you just look at the numbers it’s pretty clear.” Over the past decade, the La Jolla campus added 10,400 students, more than half of whom came from outside of California, notably China. Education experts say UCSD and other schools made the move to offset an erosion in state funding for the UC system. They were forced to try to pay bills and bankroll growth by greatly increasing the number of students they admit from other states and nations. Those students pay more than twice as much in tuition. Pradeep Khosla, who has been UCSD chancellor since 2012, denies that California students were put at a disadvantage. “No out-of-state (student) ever, during my time here, displaced a Californian,” he said in an interview. “Not once.” But facing mounting pressure from parents and students unable to secure UC berths, the Legislature adopted a budget on June 28 that orders UCSD, UCLA and UC Berkeley to make a roughly 4 percent cut in the number of undergraduates who come from outside of California. That will collectively free up 4,500 slots for California residents at those campuses over the next five years. The state will pay $184 million to cover the higher tuition money that would have come from out-of-state students. “We’re doing it in the fastest way possible, which is to buy out the out-of-state students and replace them with California students,” said Ting, chair of the Assembly Budget Committee.  The state is dealing with a big target. At UCSD, international enrollment hit a record 8,451 in 2020 — or 21 percent of the student body. It’s the highest figure in the UC and one of the highest in the U.S. The figure will drop to at least 18 percent, and maybe to 17 percent, under the new state budget. UCSD has huge programs in science, technology, engineering and the life sciences. The cut probably won’t hurt, because research in those areas is largely done by graduate students, not undergrads. But the cuts will be disruptive. And a second, potentially bigger challenge, could be coming for UCSD, which is nearing capacity. The new budget also proposes to expand undergraduate enrollment in the UC system by 6,230 in 2022-23. The plan, which has yet to be funded, specifies that all of those students must be California residents. The UC system says this is the largest proposed increase in California-resident undergraduates since 2003-04. Those 6,230 students would be spread among the UC’s nine undergraduate campuses. But a disproportionate number would likely go to La Jolla because the campus has more room to grow. For financial reasons, all of this is causing unease at UCSD, whose nearly 40,000 students make it bigger than the community of Rancho Bernardo. The campus raised a record $365 million in private donations during the fiscal year that ended on June 30. But the pandemic cost the campus about $270 million in everything from lost dorm and dining fees to patient service billings at its hospitals and clinics. And Khosla says the school didn’t receive full funding for about 2,000 of its students last year due to the way the UC system allocates money. All of this has occurred during breakneck growth. Even during the pandemic, enrollment jumped by 840. “I’m trying to have my infrastructure catch up with the students,” said Khosla, an engineer. “Student growth is easy. It happens instantaneously. Infrastructure takes three to five years to build.” The campus opened a 2,000-bed residential complex last year. But UCSD’s housing stock dropped by 2,000 due to the pandemic, which forced the school to reduce the number of students it puts in many rooms. Another 2,000-bed complex is under construction. But it won’t be ready until 2023, by which time UCSD could easily have an additional 1,000 students. The UC has been experiencing extraordinary enrollment pressures — partly because of its lofty reputation and partly because the state has reasonably good high school graduation rates. Many students meet the system’s tough entrance requirements. Interest rose further in May 2020, when the UC system announced that it will not longer consider SAT or ACT scores while making admission and scholarship decisions. The UCs ended up receiving a record 249,855 applications from students seeking to enroll in fall 2021 as freshmen or transfers. The number of prospective freshmen who applied to UCSD — a top-10 research school — increased by 18,326, pushing to a record 118,360. It won’t be known until October how many of the students who were accepted actually enrolled, and how many of them are from other states or nations. But analysts say that lots of California students who qualified for a spot won’t get one — something that makes many taxpayers and parents angry. “I know many well-qualified students who got denied from the University of California but got admission in highly selective private schools such as Carnegie Mellon, UPenn, and such universities...” Justin Thomas of Rancho Bernardo said in an email to the U-T, speaking as a taxpayer. “Why should a parent need to be double-taxed — income tax for California, and private tuition for their children!” Mick Soriano, a UCSD graduate who lives in Rancho Penasquitos said, “I would have little problem with shutting out-of-state students out entirely. But to be reasonable I’d be OK with a maximum acceptance rate of 5 percent. “Driving around UCSD, you see non-stop construction of new facilities ... Because of this and other reasons, I don’t believe that the UC system needs the out-of-state money that they claim they need.” Assemblyman Ting gets annoyed when people suggest that the Legislature has been stingy when it comes to the UC. “We have increased the UC’s budget every single year since I’ve been in the Legislature, starting in 2012,” he said. “There are clearly ways that the university could have become more efficient.” Over a longer period, state support is down. In the mid-1970s, about 18 percent of the state’s budget was spent on higher education. By 2016-17, the figure was 12 percent, and the UC system had taken the big hits, with funding per full-time equivalent student dropping from $23,000 to $8,000, according to the Public Policy Institute of California. There’s also tension over the way the UC has handled public funds. Ting pointed to a 2017 state audit that concluded the UC Office of the President had “amassed substantial reserve funds, used misleading budgeting practices, provided its employees with generous salaries and atypical benefits, and failed to satisfactorily justify its spending on systemwide initiatives.” That outraged lawmakers, some of whom also became upset by complaints from the parents of high school students that the UC system was overlooking their children in favor of out-of-staters who could pay higher tuition. Some of the attention inevitably focused on UCSD, with its high international enrollment.

“Will we find enough Californians to replace the non-residents? The short answer is yes,” Khosla said. “We will certainly find enough Californians. I am not losing sleep over that. “They could be on the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) side. They could be on the non-STEM side. I want my school to be more balanced and holistic.” Source: The San Diego Union - Tribune |

HoursM-F: 7am - 9pm

|

Telephone+1 613 981 1809

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed